Sep 17, 2020 · 7 min read

Q&A: How Do We Increase Diversity in STEM? Meyerhoff Program Provides a Model

In April 2019, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative launched a $6.9 million effort to help increase the diversity of STEM students on college campuses. The grants are enabling both the University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego) and the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) to replicate and expand aspects of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County’s (UMBC) Meyerhoff Scholars Program.

Since it began in 1988, the Meyerhoff program has seen astounding success. Alumni have earned over 340 Ph.Ds, including 64 M.D./Ph.D. degrees, as well as over 150 M.D. or D.O. degrees and over 300 master’s degrees (primarily in engineering, computer science, and related areas).

We spoke with Dr. Freeman Hrabowski, President of UMBC and one of the founders of the Meyerhoff program, as well as Dr. Lola Eniola-Adefeso, a past participant of the program and current professor of chemical engineering at the University of Michigan. The two spoke about their experiences with Meyerhoff, what they believe makes it so special, and the pressing need to support Black and Latinx students in STEM fields.

Where did the idea of the Meyerhoff Scholars Program originate?

Dr. Hrabowski: The challenge we faced in the late ‘80s was that many students, of every race, came to UMBC to become physicians or major in science. Unfortunately, the vast majority of African-American students were not doing well. So we started looking for any institution in the country, beyond Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), that could show us examples of Black people excelling in science. We could not find one.

So we decided to build one. Bob Meyerhoff provided incredible, generous support. We rooted the program in four pillars of success: high expectations, a strong sense of community, active participation in scientific research, and faculty who are deeply invested in their students.

Meyerhoff starts six weeks before the academic year even begins. Before their freshman year, students get familiar with the rigor of college-level instruction and start forming their community. Students go through their classes, research, internships, and study abroad experiences together—and gather regularly for mandatory “family meetings” that bring the entire group together. And the program continues through all four years of college.

In the years since Meyerhoff’s founding, we’ve seen the program change as we listen and learn from our students’ experiences, and identify faculty who want to get involved. But it’s always been rooted in our values of excellence, high expectations, and community.

Was that culture of high expectations and community part of your experience, Dr. Eniola-Adefeso?

Dr. Eniola-Adefeso: Absolutely. I didn’t have the experience of being in a privileged high school program; I was literally a kid off the street. So my first Meyerhoff family meeting was overwhelming, in the sense that I went from seeing maybe three or four Black STEM students in my high school calculus classes to seeing 50-plus Black students in science and engineering in the same room.

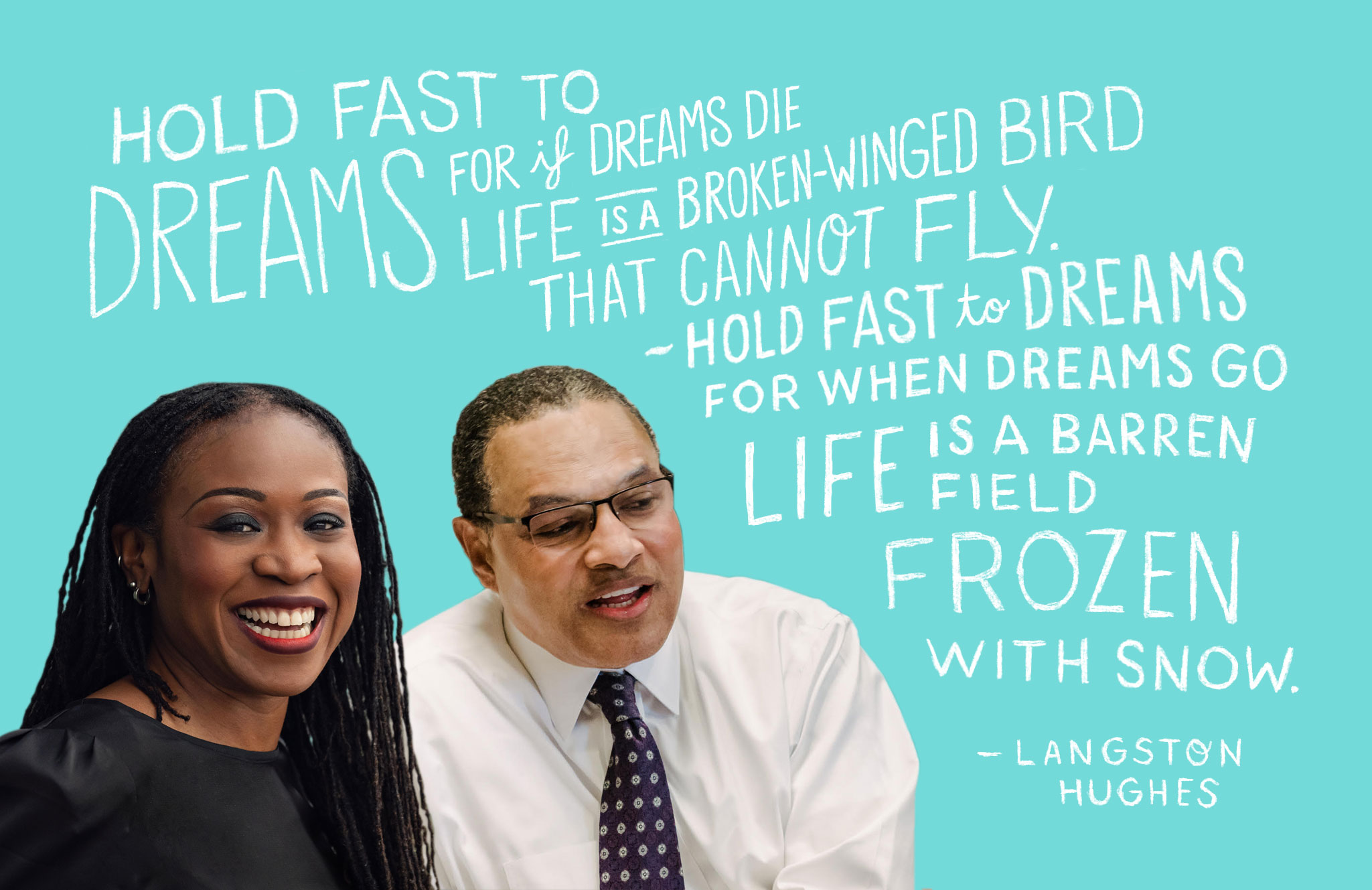

It was also the first time that I met Dr. Hrabowski. He comes into the family meeting, and he’s talking about all kinds of stuff that I’ve never heard before, about achieving success and being at the top of your class. Towards the end of the meeting, we started reciting “Hold Fast to Dreams” and I just started crying.

That concept of dreaming and having a vision of your future—unrestricted by what others have said you should be—that was powerful. And so was the idea that you can build things that excite you, even though they may be outside the norm. That was the first time I was exposed to that feeling, and the moment that really shifted my trajectory.

Dr. Hrabowski: That’s the belief we want all our students to have. Lola is amazing; she really is. She’s not only the best in research and now a full professor of chemical engineering at Michigan —she also has the Meyerhoff mindset: “Of those to whom much is given, much is required.” She is paying it forward. She regularly hosts students from UMBC at her lab, and welcomes Meyerhoff program graduates who go on to Michigan because of her example.

An important part of our philosophy is not just about helping students individually get to the top; it is about producing excellence. And we talk about inclusive excellence; excellence for not only African Americans, Latinos, but all people who really get it, who have an attitude that says, “I want to help the students of color when I get to my lab.” We need that.

That concept of dreaming and having a vision of your future—unrestricted by what others have said you should be—that was powerful.

We see Meyerhoff Scholars carrying that ethos forward to make an impact in the world. What are some of the exciting projects graduates are working on?

Dr. Hrabowski: Right now, one young woman making history is Kizzmekia Corbett, who is working on a vaccine for COVID-19. She graduated from UMBC, went on to Chapel Hill and is now a researcher at the National Institutes of Health. She’s leading the team that has invented the vaccine that Moderna has in phase three trials right now. It’s huge.

Kafui Dzirasa is also one of our most outstanding graduates. He just won the Young Investigator Award from the Society for Neuroscience for research that’s changing the way we think about depression. But here’s the most amazing part: as a professor at Duke, he has in his contract a clause that says he can come back to UMBC one day a month to mentor Meyerhoff students. I’ve never heard of that before. He comes back every month to mentor, and now he has three or four Meyerhoff Scholars at Duke whom he’s personally recruited. That’s the philosophy of Meyerhoff. It is about the nobility of paying it forward.

Dr. Eniola-Adefeso: I have a Rolodex of Meyerhoff alumni, 80 percent of whom are African Americans, all of whom are changing the world. Whenever somebody asks me for a recommendation, I can almost always connect them with an African American person with a PhD in that field. I don’t know many people in the world who can say that.

Despite this success, we continue to see systemic disparities in education. What’s your message to people working to make progress in other schools, especially as the Meyerhoff Program expands to UC Berkeley and UC San Diego?

Dr. Eniola-Adefeso: I think the need that existed when the Meyerhoff program began still exists now. Having been a faculty member for the last 15 years, I still see a lot of our students in engineering, in my institution and across others, struggle when they’re in the minority. There are still not many who look like them. There’s no program like Meyerhoff to bring them all together. We need to change that. And I know we can.

Dr. Hrabowski: We have to keep pushing institutions to come up to the plate and do much more to support students, especially in science and engineering. It’s going to require changing the culture. If we’re truthful with ourselves, we know we have a lot of work to do.

And that’s the point of Meyerhoff: showing that even though there’s more work to do, it can be done. Showing that the number one investigator in neuroscience in the world, and the inventor of a COVID-19 vaccine, can be Black. That’s what we have to keep showing.