Nov 29, 2018 · 8 min read

Working to Solve a Family’s Medical Mystery

The water in the Duke Children’s Hospital Pediatric Bone Marrow unit is ridiculously delicious. It has to be. The floor is full of children who have had their immune systems suppressed so their bodies don’t reject the transplants that are keeping them alive. One of my brothers once compared it to entering a submarine. To maintain the sterile unit you are required to open one door, sit in an airlock, wait for that door to close, wash your hands for 30 seconds and then open another door. You are given little booties to cover the bottom of your shoes and food is monitored carefully. The water in the unit is extremely filtered to make sure nothing harmful gets through. And it was the clearest, coldest, freshest, most delicious water anyone in my family had ever tasted. It made our daily visits slightly better.

Five years ago, the hospital agreed to let my little brother use one of the available rooms in the Pediatric Bone Marrow unit even though he wasn’t in line for a transplant. He had been transferred from the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) after breaking the record for longest PICU stay in Duke history. My brother’s brain and body were being attacked by something unknown and they were just able to manage it enough to keep him alive.

My brother went home four months later. It was his sixth hospitalization in three years.

Sequencing can help take bias out of traditional diagnostic testing and identify pathogens that we have never seen before.

One of the first signs that something terrible was happening came one evening in 2008. My previously healthy and normal 13-year-old little brother forgot the rules to his favorite card game and kept trying to leave the house to find people he believed were coming after our family. My parents brought him to the hospital the next day, panicking as they watched their child forget the date and lose his ability to draw simple shapes. The doctors who saw him initially were convinced he was suffering from a psychotic breakdown or the first signs of schizophrenia. My mom — who just happens to be a child psychiatrist — insisted that his neural degeneration came on too quickly, but the doctors wouldn’t listen. While they hadn’t seen something like this before, they still tried to send him home. My parents were hysterical and at the end of their rope. Not knowing what else to do, my mom reached out to a colleague who was a pediatric neurologist. He listened to my parents, ran more tests, and confirmed what my parents already knew — that something seriously neurological was going on. My brother was immediately admitted to the hospital and the search for an answer began.

Everyone loves a medical mystery from a distance. What you don’t usually hear about are the endless days sitting with someone you love, hoping that you will learn to understand what kind of beast they are fighting and what you can possibly do to help them fight back. I learned to recognize the sound of my parent’s coming home at 1 am after visiting hours were over. They were exhausted after a long day of trying to understand, along with the doctors, what was going on with their son — my little brother — knowing that time was running out. Our ignorance about the disease carried a high price and we knew it.

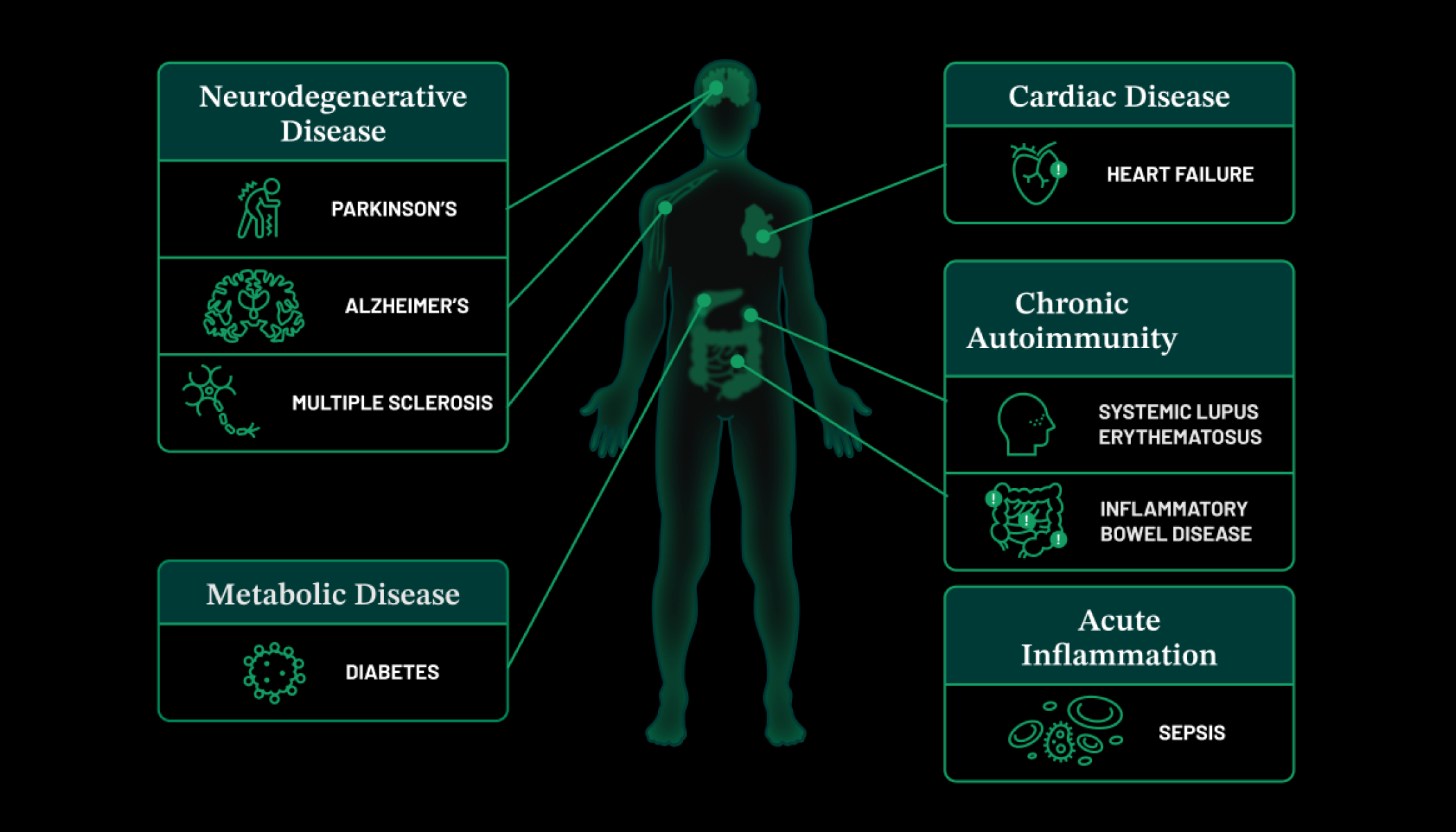

Finally, after months of uncertainty, the doctors were finally able to give the beast a name — Autoimmune Encephalitis. This illness can be triggered by an unknown pathogen and triggers overproduction of a key antibody that current tests cannot identify. This antibody attacks the brain and causes delirium and loss of brain function. When my brother was diagnosed, the disease was just starting to be understood by the larger scientific and medical community. Luckily, a treatment was available. He got better and left the hospital.

Then, two years later, he relapsed. A new, unknown agent had kicked off an antibody response and the battle started all over again. But this time, we were much less helpless. We would not give up hope and did everything we could to better understand this disease. My brother has relapsed multiple times since his first diagnosis and each time is hard but it’s somehow become more normal and routine. My parents found a community of other families and doctors looking for answers and joined this group to share personal experiences, small victories, and tragic losses.

Through these relationships and our experience, we were able to understand how lucky and privileged we are. My family home is a five-minute drive from Duke hospital — one of the best medical facilities in the world. That means they could visit their other children and sleep in their own bed after spending long days at the hospital with my brother. My mom is also a doctor at Duke and was able to reach out to her connections to ask for new medical opinions and advice. She could communicate with the doctors and advocate for treatments and support that my brother needed to survive. My parents each had employers that allowed them to take off time to care for their son. They each had healthcare to cover the massive hospital bills and they knew how to get doctors to advocate for insurance coverage. We had a community of friends and family who showed up to help in any way they could over and over again. My brother now is able to have much of his treatment at home. When he last relapsed, we were able to have a nurse sit with him at night when he was agitated so my parents could sleep a few hours. Most importantly, we were able to figure out what my brother had so he could get back to running his fantasy football team with an iron fist.

The road was full of exhaustion, pain, and many bouts of discouragement—but I can now offer something of value from this experience. Now, in my work and life, I’m always asking myself how I can make sure more people have the ability to treat and care for their children—no matter what.

On the other side of the country at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), brilliant doctors and scientists — including Joe DeRisi and Michael Wilson — were trying to understand what pathogens trigger overactive antibody responses — something I was personally familiar with but instead of testing for a range of specific diseases, they were trying to leverage DNA sequencing technology and computational tools to detect what is otherwise undetectable. Sequencing can help take bias out of traditional diagnostic testing and identify pathogens that we have never seen before. This technology and approach have already proven to be hugely impactful, but access has been limited to scientists and doctors working with Joe, UCSF or their collaborators. This work continued at the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub when Joe started as the co-president and spun up the infectious disease program. As a member of CZI’s product team, I was given the opportunity to work with Joe and his team.

One of the goals of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s tech team is to partner with experts to build tools that weren’t previously possible. By bringing together the incredible engineers on my team with the brilliant scientists at the Biohub, we are able to scale access to their scientific discoveries for a larger audience, breaking down barriers and building local capacity. Over the past year, the two organizations have built a product called IDseq that helps scientists and doctors make sense of genetic data so they can identify and discover an infectious disease that can then be verified and tested in the lab. We are working with our partners to implement this technology and train scientists in the places that need it the most. Although this product wasn’t what led to my brother’s diagnosis, I believe it will provide support for doctors and scientists around the world facing similar challenges.

Now, through the luck of knowing the right people, my family is planning to send his samples to my colleagues who would use the clinical equivalent of IDseq to see if they can find an answer we may have missed.

Our family was lucky enough to have access and support across the medical community, but many others are not as fortunate. At CZI we are hoping to bring the kind of access that we were afforded to everyone, so luck is not part of the equation.

The medical progress since my brother first got sick eleven years ago is staggering and inspiring. Knowledge about Autoimmune Encephalitis and related diseases is growing rapidly. We are starting to understand how and why diseases act the way they do, not just identify them. I realize that the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s scientific goals are ambitious – to support the science and technology that will make it possible to cure, prevent, and manage all disease by the end of the century. Based on the progress I’ve seen, I believe we’re taking steps in the right direction.