Jul 6, 2022 · 8 min read

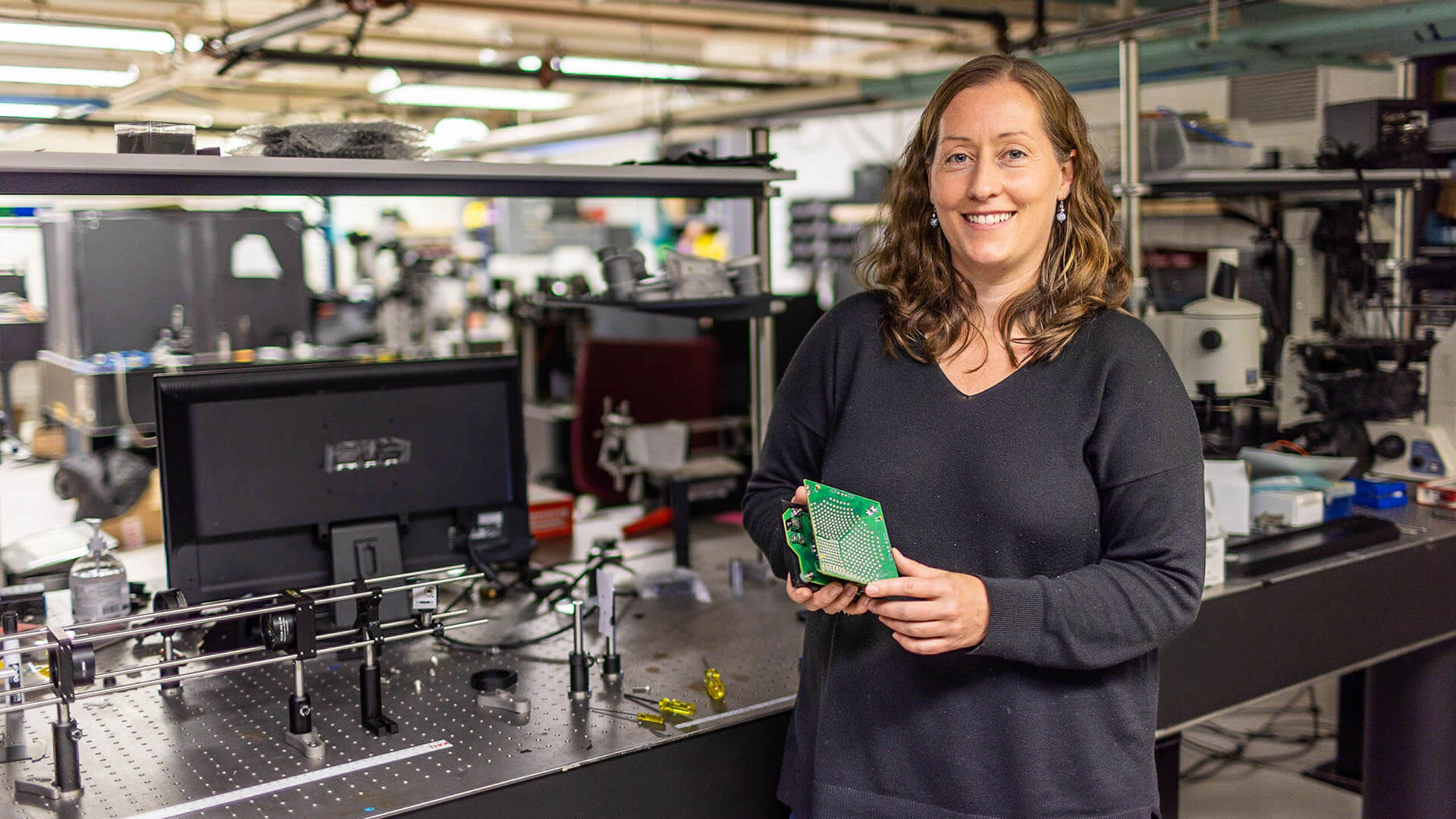

A Day in the Life of an Imaging Scientist: Laura Waller

Scientist Laura Waller is pushing the frontiers of imaging. Explore a day in her life and lab, building microscopes that help neuroscientists understand the brain.

The microscopes in Laura Waller’s lab are not the simple light microscopes you used in school to peer at pond water or a human hair. In her designs, computers, rather than lenses, do most of the work.

Laura is a rising star in the field of computational imaging. It combines the hardware used in microscopes with the kind of software you find in a smartphone, letting you digitally enhance a photograph — such as adding a filter or frame. However, Laura is not focused on taking better portraits. Instead, her microscopes are designed to help other scientists see biology in new ways and in exquisite detail. Her microscopes can, for example, capture the simultaneous activity of large groups of brain cells in three dimensions, a feat that could help neuroscientists understand how the brain functions.

I really love this field, because it’s very creative. There are new ideas and new things to think about all the time, but it’s also grounded in real applications

Laura studied engineering and computer science during a joint bachelor’s and master’s degree program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she also played soccer. She stayed for a Ph.D. that combined her interests: image processing and optics. At the time, computational imaging was just taking off. She began to design software and hardware to detect light or manipulate light, applying it to microscopes and the hidden world they can reveal.

In 2012, Laura started her own lab at the University of California, Berkeley. Fittingly, the university’s motto is “Let there be light” or “Fiat lux” in Latin. She now holds the Ted Van Duzer Endowed Professorship in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. Laura is also part of the CZ Biohub Investigators Program and is the recipient of a Deep Tissue Imaging grant through CZI’s Imaging Program.

Laura is still pushing the frontiers of imaging while juggling parenting and the pandemic. She has two boys, ages 6 months and 3 years, and worked from home through much of the last two years.

After 10 years as a principal investigator, she says her fascination with optics persists. When she is teaching at the university, she often demos optical illusions for her students, saying, “It’s not magic, it’s science.”

Follow along to learn more about a typical day in Laura’s life as an imaging scientist and mother.

Starting Early

With a baby and a toddler, my day starts early. I also do my best thinking in the morning — when there’s not a million emails coming in. That’s when you can get stuff done. My husband and I trade off who is taking care of the kids before and after work. If I go into the lab, I try to stay a little later than I would have before the kids were born. But I also work from home a couple of days a week. I’m not teaching this year because I’m on maternity leave, which gives me more control over my schedule.

Mentoring and Mothering

During COVID, we decided our house was too small for two kids and two people working from home, so we moved to a much bigger house in the suburbs. I have a nice setup now, and I’ve actually really appreciated working from home. I can take a 5-minute break and play with my kids. And I’ve been able to ease back into work. My baby was on Zoom a lot during his first four months. He would be sleeping on my shoulder while I had calls with my students. It was really amazing and my students seemed happy to see him!

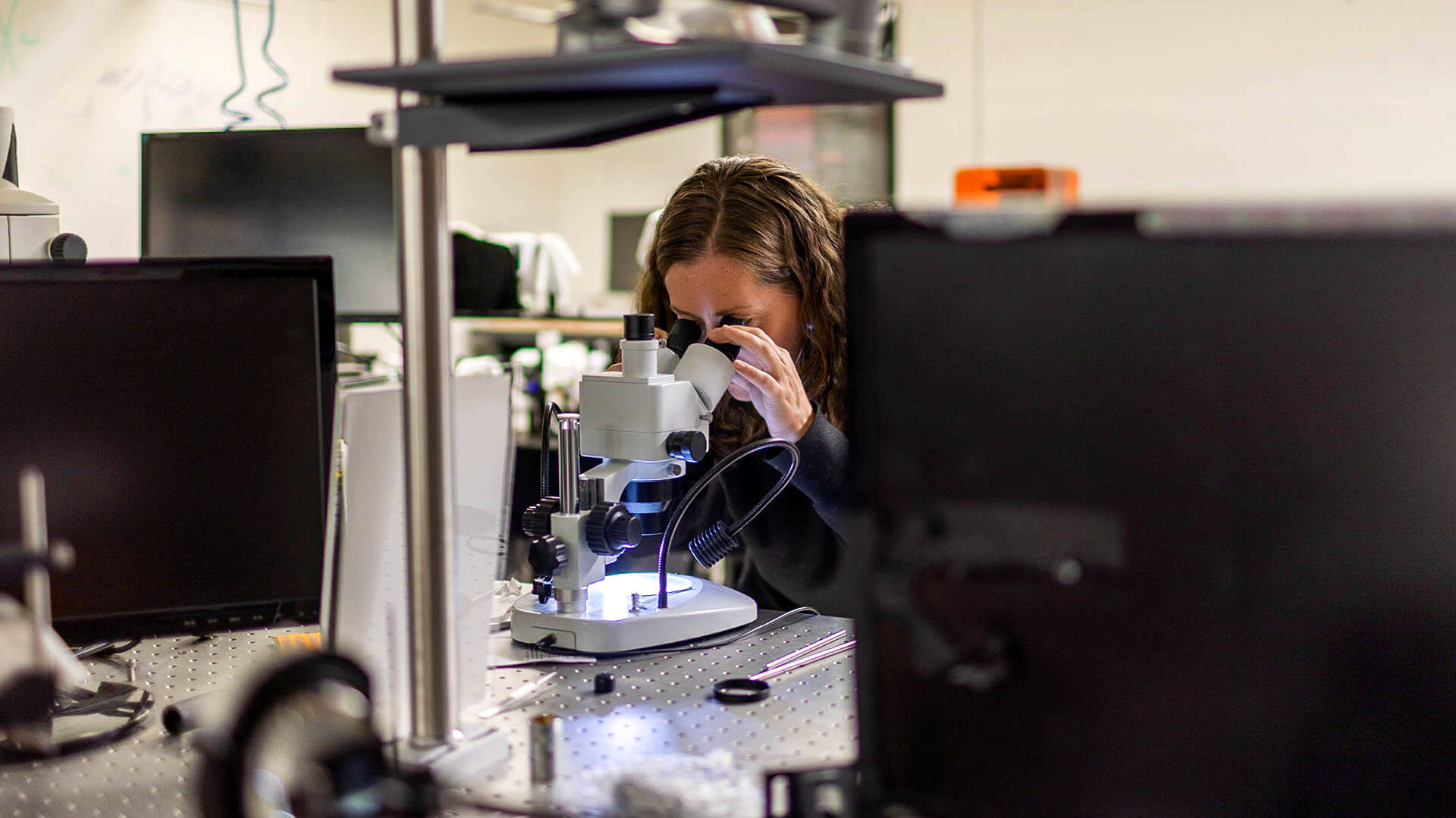

Making Microscopes

At my lab, we design and build new microscopes. Sometimes we’re trying to design a microscope tailored for a very specific application. Sometimes we are working on general-purpose microscopes and developing and testing new ideas. What is really exciting about the field of computational imaging is we get to push the limits of imaging science and then figure out what it’s useful for. Sometimes that mode of research allows us to come up with entirely new ways of doing things that make a bigger impact than if we tried to use existing methods to solve existing problems.

Also read: The Past, Present and Future of Medical Imaging

Hacking for Science

In the lab, we have six optical tables with a couple of microscopes on each one. Some are commercial microscopes and some are homemade. I like hacking things and being thrifty. So sometimes we make hardware modifications to commercial microscopes because that makes our methods accessible. Most researchers have commercial microscopes, so if you can just make a modification to that, it’s easier for them to adopt the technology. We also have an electronics workstation, a 3D printer for making mechanics, and a shelf of test objects that we use to test out various cameras.

Testing New Tech

The CZI Science network has been a great way to find applications that can benefit from the things that our microscopes can do. We’ll develop a prototype, then I’ll give a talk about it at a CZI grantee meeting and say, “Here’s what we can do. What’s it good for?” Inevitably, I’ll have five other grantees come up and say, “Oh, I have this problem imaging proteins inside cells. Do you want to try it?” So it has been so great for my group to test our ideas.

Also read: Expanding the Frontiers of Imaging

Cultivating Collaboration

My lab has a really great culture, especially in the office where students hang out and talk about science. But toward the beginning of the pandemic, our new students didn’t get to properly meet everyone and learn how to do stuff in the lab. It wasn’t ideal. I saw a precipitous drop in students saying, “Oh, this other person in the lab knows how to do that, so they’re gonna help me,” just because they weren’t connecting with each other. And I don’t think that’s come back to baseline yet. I hope the lab will get back to the more vibrant, collaborative culture that we had before.

Managing Meetings

I usually have lots of meetings with my grad students and postdocs — faculty meetings, committee meetings, and lunch events to meet with visitors. We just started going back in person for our research group meetings and it’s just so much better to have a real live discussion. Ideally, I try to have some days when I have the whole morning to work on a research paper. So a lot of my work is managing people, reading, editing or reviewing papers, or doing service work like organizing scientific conferences.

Practicing Open Science

Success to me is really about other people using our stuff and trying out our ideas. We’re designing methods and we want other people to use them, right? That is why I say that our biggest success stories are not that we wrote a bunch of Nature papers; it’s that we made a method that other people used to write a bunch of Nature papers! So the easier we can make it for someone else to use them, the better. We work very hard to make our methods accessible, which means the software code is available online, the hardware parts are fairly cheap and easy to find or build.

Also read: How Open Source Increases Access to Computational Tools for Every Scientist

Spending Time with Family

Our new house has a pool, so my 3-year-old is getting pretty good at swimming. We also have some good optics books for kids! One of them talks about how to make rainbows with a hose, so today my son was running around outside with the hose looking for rainbows. I mean, he’s only two but he’s learning a little bit.

Staying Active

When I’m not working or parenting, I like spending time outdoors. This summer, I’m going on a hiking trip to celebrate my friend’s 40th birthday. I’m joining her for a few days while she completes the John Muir Trail, a 200-mile hike up the coast of California. I also just started playing soccer again. When I was a student, I played varsity soccer, so I’ve been trying to get back into it.

More Content Like This

Did you enjoy this story? Explore more from our Day in the Life series.