Oct 13, 2021 · 6 min read

A Day in the Life of an Early-Career Researcher: Abbas Rizvi

Empowering early-career researchers is one of our commitments at CZI. This means providing talented scientists still at the beginnings of their careers with the resources and the community they need to take risks and pursue their boldest ideas.

We recently sat down with Abbas Rizvi, an associate research scientist at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute, to explore what a day in the life of an early-career researcher looks like.

I try to put people first. This connection between the personal and professional builds community and makes science stronger.

As an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, Abbas investigated photosynthesis using spectroscopy. While a graduate student at Harvard, he developed an interest in the identities of cells. From starting as a project member for an earlier CZI grant, he’s now, a co-principal investigator on a $1.5-million CZI grant, where he’s been training his own team and building out his lab space in pursuit of an ambitious goal: creating a cellular atlas of the spinal cord.

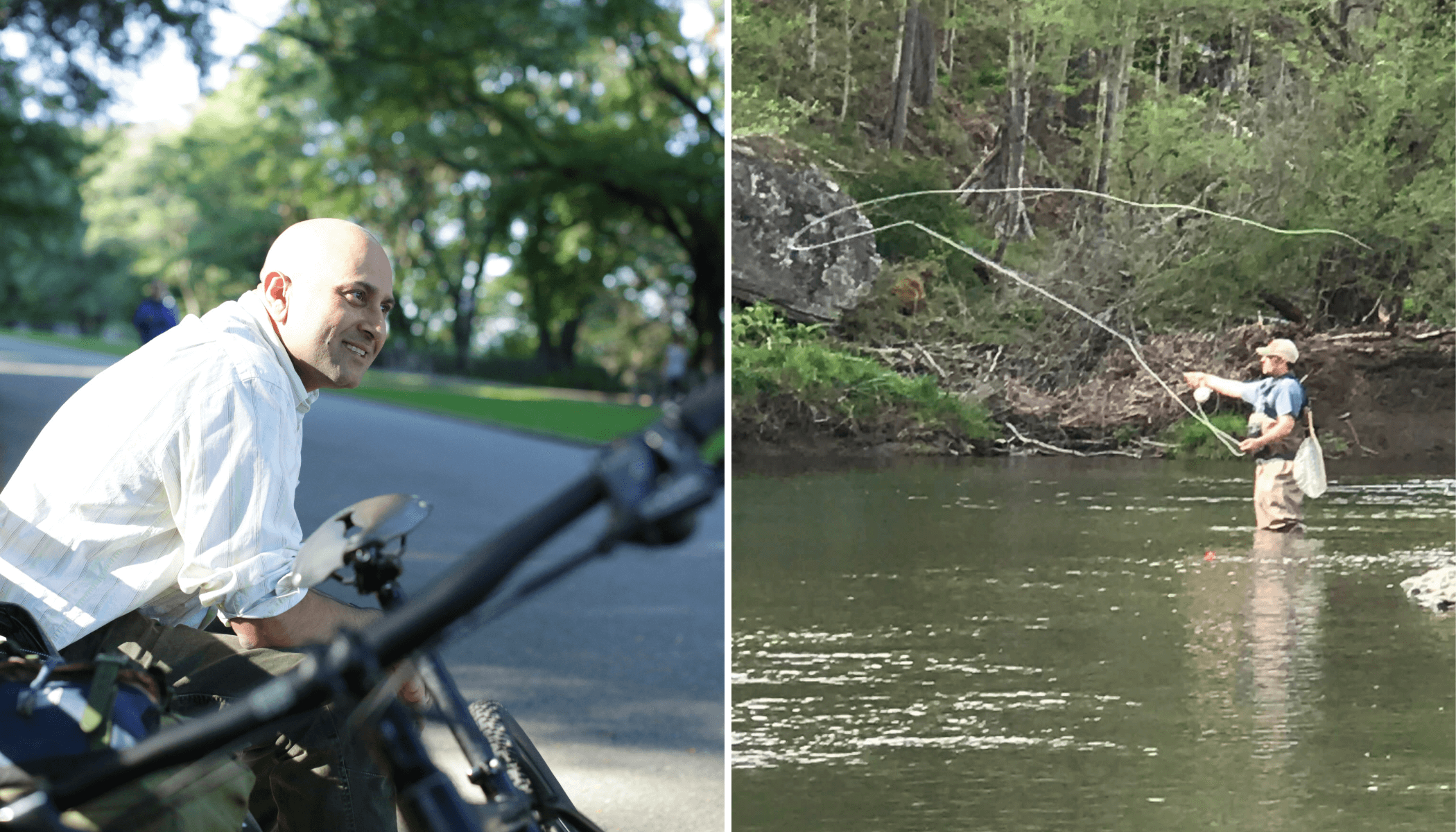

The days of an early-career researcher can be challenging — and long. But for Abbas, research is a lot like fly fishing. He doesn’t expect to catch a big fish every time he wades out with his pole into the Delaware River. Nor does he think every experiment will work when he fires up his cell sorter in Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute. Abbas approaches both fishing and research with a patience that comes from love of the experience itself — the feeling of flow that both activities provide.

Read on as Abbas describes a day in his life.

Breakfast and Bicycle

I usually wake up pretty early to make breakfast for my son. He’s 8, and it’s important for me to spend a lot of time with him in the morning, especially given everything we’ve been going through with COVID. We talk about his day. We talk about my day. Then I bicycle to the Zuckerman Institute through Riverside Park. It’s a scenic 15-minute ride near the Hudson River, a route that a lot of people use to commute.

Teaming Up to Map the Spine

Each day in the lab begins with a meeting of my team, a motley crew of experimentalists I’ve trained. Supported by CZI’s Seed Networks for the Human Cell Atlas, we’re focused on mapping every cell in the spinal cord. It’s a huge undertaking. We talk about victories. We talk about difficulties. Someone might say, “I’ve been having trouble purifying this enzyme,” and everyone chimes in with ideas. We approach everything in this collective, holistic way.

Also read: Biology’s Most Ambitious Map Yet: The Human Cell Atlas

Theorists Weigh In

On some days, we invite our collaborators in theoretical neuroscience to join us. We update them on our experiments. They look at our data and tell us, “Wow, this is really exciting and here’s why,” or “I’ve noticed something that we can improve in the experiments.” So there’s this critical feedback loop between theory and experiment that drives what we do. We might also meet with other researchers around the university, collaborators at other institutions, or scientists I’ve connected with through the CZI Seed Networks.

One-on-One Connections

Research can be difficult. So I also make it a point to sit down with my team members one-on-one every week to talk about how they’re doing and anything interfering with their ability to do science. I offer support on the tough days — when the experiments don’t work. With the pandemic, everyone has their challenges, and it’s important to make sure everyone can give voice to that. I try to put people first. This connection between the personal and professional builds community and makes science stronger.

Mentoring Scientists in the Making

I’ve also been mentoring a Columbia College student as part of the university’s Black Undergraduate Mentorship Program. I’ve been fortunate enough to have good advisers during my career — senior scientists who taught me how to embrace creativity or to laugh in tough situations. So passing along what I’ve learned feels like the right thing to do. It’s incredible to see her now getting ready to start her first research position in another lab a few floors up from mine.

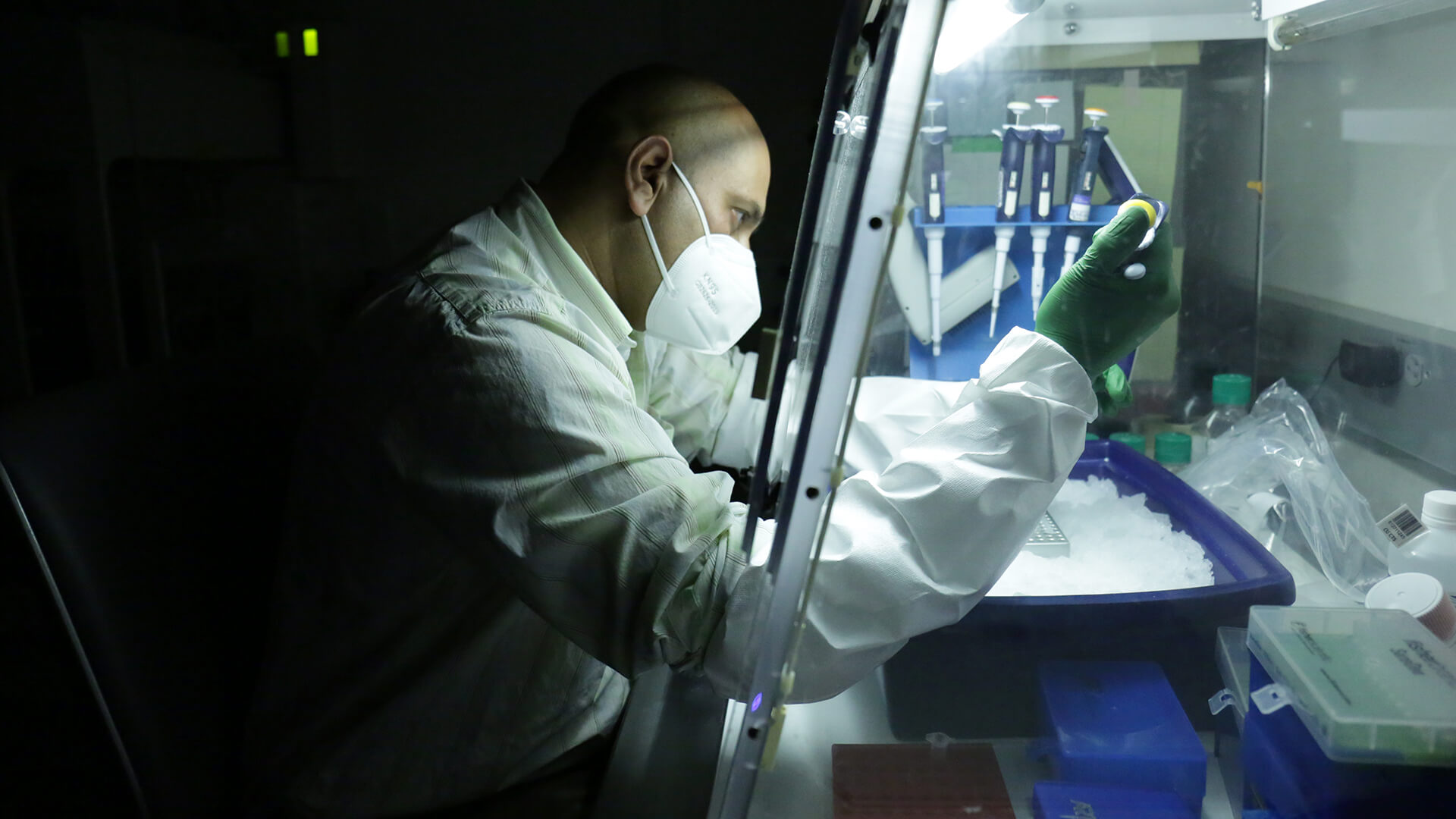

Fixing the Equipment

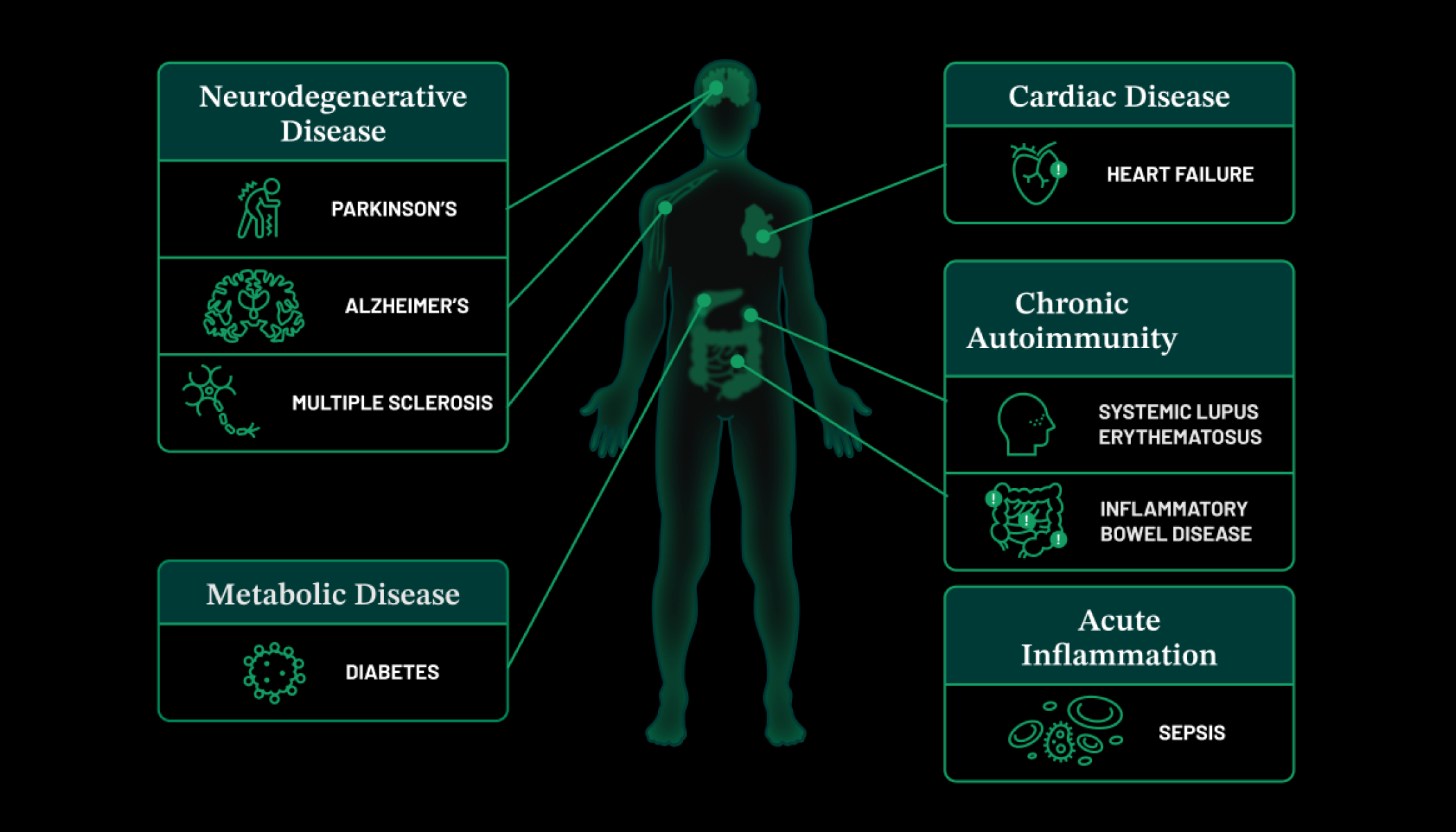

During the afternoon, you might find me in my lab, tinkering with equipment or doing a key set of experiments. For instance, we recently had a power outage that damaged the flow cytometer we use to sort out cells — I had to fix it. I’m proud of the space we’ve built here. It started with used equipment, demo equipment — whatever I could scrounge, take apart and fix up. I purchased my first liquid handling unit on eBay. Now we have a whole array of tools for locating and isolating individual cells in human spinal tissue en masse and looking at patterns of gene activity to identify them — as part of the Human Cell Atlas project mapping the identity and functions of all 37 trillion cells in the human body.

Family Dinner

For dinner, I hop on the bike for a 15-minute ride back home to my family. We work on my son’s homework. We might take a bike ride together. I get him into bed. Then it’s back on the bike to the lab for a late night. Sometimes midnight. Sometimes 2 a.m. Whatever it takes.

Moving Forward Together

The experiments we do are difficult. Some of them run for 40 hours straight, and we take them in shifts. It’s not always easy. But it’s worth it. When I started all of this, it was just me and an idea. Being able to build community — locally, nationally and abroad — has changed the game. I’m not angling by myself in the Delaware River. I’m never alone when up against the problems that pop up in this work. I have a team. And we’re all learning from each other as we explore the fundamental biology of the human body and empower the fight against disease.

Check our recent Medium post to learn more about the joys and challenges of being an early career researcher. It features several scientists offering their perspectives and advice on navigating a career in science.

More Content Like This

Did you enjoy this story? Explore more from our Day in the Life series.