Jul 9, 2024 · 11 min read

How Technology is Democratizing Genetic Research for Rare Diseases

Interview with the Broad Institute’s Samantha Baxter about a new tool to estimate genetic prevalence.

An estimated 5% of the global population is born with or develops a rare disease over their lifetime. One of the biggest challenges for these patients is obtaining a genetic diagnosis, which is crucial for pursuing appropriate treatment options (if available) and ultimately improving their quality of life. Despite significant advancements in genetic diagnostic technologies, many rare disease genes remain unidentified, contributing to an average “diagnostic odyssey” of over five years for affected families and many patients never receiving a diagnosis. Without a diagnosis, patients cannot access treatments, if they exist, or join and form patient communities.

Worldwide, rare disease communities are tackling this challenge by forming robust networks and research partnerships in their quest for cures. CZI’s Rare As One Network supports these patient-led organizations by providing essential resources and tools as they advocate for and participate in research.

A key partner in this effort is the Rare Genomes Project, a patient-driven research effort housed at the Broad Institute of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University and part of the National Human Genome Research Institute’s GREGoR Consortium. Led by genomics experts in partnership with rare disease patients, families and advocates, the Rare Genomes Project aims to make the latest advances in genomic sequencing accessible to those with rare and undiagnosed conditions and ultimately provide diagnoses.

The Rare Genomes Project primarily recruits patient participants through social media and rare disease foundations, sequences and analyzes their data, and returns results directly to participants and their physicians. This approach puts these critical diagnoses directly into the hands of patients and their physicians while sharing de-identified genetic data with the broader research community.

Another critical hurdle the Rare Genomes Project addresses is estimating the prevalence of rare diseases. This understanding is vital for enabling and scaling patient-partnered research, as communities need to know how many people globally may be affected by their disease to develop effective strategies to identify and reach all affected individuals and families and justify drug development efforts.

GeniE aims to broaden participation by making data accessible to people with diverse backgrounds and expertise. Previously, only those with specific computational training could analyze this data, potentially missing valuable insights. By making GeniE user-friendly, we hope to encourage more individuals to engage with the data, fostering new ideas and collaborations.

Since 2021, the Rare Genomes Project has been developing a prevalence estimate calculator for autosomal recessive diseases. In June, this tool, named the Genetic Prevalence Estimator (GeniE), was officially launched. Developed in collaboration with 11 Rare As One Network grantees and other patient-led rare disease organizations, GeniE helps estimate disease prevalence, inform outreach strategies, and identify regions where undiagnosed patients might be found at higher frequencies to build inclusive patient communities.

GeniE democratizes the process of estimating genetic prevalence for rare recessive diseases by eliminating the need for computational expertise, making it accessible not just to genomics experts but also to patient communities and other stakeholders.

We recently spoke with Samantha Baxter, a genetic counselor and associate director of genetic and genomic data sharing at the Broad Institute’s Translational Genomics Group (TGG), to delve into the motivations and efforts behind the creation of GeniE. Baxter supports TGG’s efforts to analyze, share and protect the genetic information of thousands of patients and families seeking answers about undiagnosed rare diseases. She was also a vital part of the team that launched GeniE, contributing significantly to its development and implementation.

What distinguishes the Rare Genomes Project from other genome research efforts for the rare disease community?

Samantha Baxter: The Rare Genomes Project is unique because it combines cutting-edge research with a deeply personalized approach. We intentionally keep our project small to provide a hands-on experience, ensuring we can spend quality time with each family during enrollment and throughout their involvement. This close interaction helps us understand their needs better and offer tailored support.

The variety of molecular tools we use also sets the Rare Genomes Project apart. We provide genome sequencing, which helps identify single nucleotide variants and small insertions or deletions (indels) — these are small but significant changes in DNA. We analyze structural variants, which involve large alterations in the genome, such as the deletion or duplication of multiple genes. Additionally, we offer mitochondrial sequencing to examine the DNA within mitochondria, tandem repeat analysis to study regions where short DNA sequences are repeated many times, and RNA sequencing to gain insights into gene expression and regulation.

What is genetic prevalence, and how does estimating it help rare disease patients?

SB: Genetic prevalence is the estimated proportion of a population that has a causal genotype for a genetic disease. In simpler terms, it estimates how many people might have the genetic cause of a specific condition.

Estimating genetic prevalence is incredibly powerful. It estimates potential cases but doesn’t specify the exact number of diagnosed individuals. By combining data from various sources — such as newborn screening incidence, electronic health records, patient registries, and genetic prevalence estimates — we can start to get a clearer picture of the disease’s actual impact.

While no estimate is perfect, our goal is to refine our understanding continuously. We aim to get closer to the true number of affected individuals, learning from any mismatches to gain deeper insights.

Why is the prevalence estimate calculator tool, GeniE, important?

SB: Developing GeniE has been a passion project of mine for six years. It began around the same time the Rare Genomes Project began enrolling participants, initially sparked by a partnership with a pharmaceutical company seeking to understand its market by estimating genetic prevalence.

The project took on new significance when I met two rare disease advocates, Jocelyn Duff and Kasey Edwards. These “rare disease moms” highlighted the urgent need for patient advocacy groups to answer a critical question: “How many of us are there?” This realization struck me deeply. I had the tools to help, but the process was lengthy and required computational expertise, which limited its scalability and accessibility.

Listen now: Finding Rare Disease Treatments: 2 Patient Leaders Share Their Stories

Inspired by Duff and Edwards, I envisioned an online tool that could automate complex processes and calculations, making it easy for anyone to use. GeniE was born out of this need to democratize the process.

GeniE aims to broaden participation by making data accessible to people with diverse backgrounds and expertise. Previously, only those with specific computational training could analyze this data, potentially missing valuable insights. By making GeniE user-friendly, we hope to encourage more individuals to engage with the data, fostering new ideas and collaborations.

The tool transforms a process that once took months into something that can be done in about five minutes. While some follow-up work is still needed, GeniE handles the challenging bioinformatics — significantly speeding up and simplifying the task.

This achievement is a team effort at Broad, including Nick Watts, the initial software developer who brought GeniE from idea to beta; and Riley Grant and Josephine Lee, who have developed the tool over the past year, bringing it to its official release. The team also includes Moriel Singer-Berk, lead variant curator; Katie Russell and Carmen Glaze, variant curators and liaisons with advocacy groups; and Heidi Rehm and Anne O’Donnell-Luria, principal investigators.

Some of the patient-led organizations that helped develop GeniE include members of the Rare As One Network, including the APBD Research Foundation, Association for Creatine Deficiencies, Congenital Hyperinsulinism International, Cure CMD, DADA2 Foundation, Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome Network, INADcure Foundation, TANGO2 Research Foundation, TESS Research Foundation, The Yaya Foundation for 4H Leukodystrophy, and Usher 1F Collaborative.

Watch more: How Patients With Rare Diseases Are Accelerating Groundbreaking Research for Their Communities

How have you partnered with Rare As One grantees in the study? And how are the Rare As One groups leveraging the findings in their work?

SB: The Rare As One grantees have been true collaborators from the very beginning. They had significant input on the types of data they wanted to see and how they preferred to visualize this information. Their feedback was crucial in designing GeniE to ensure it met the community’s needs and made the tool globally accessible.

As for how the Rare As One groups are leveraging the findings, we’ve ensured they and other patient organizations collaborating with us are the first to receive the results. This allows them to decide the best way to use the data based on their community’s needs. Some groups prioritize quick publications to have something to cite, while others use newsletters to inform their community about the prevalence of their disease. Having a validated method and credible statistics has been powerful. It provides a solid foundation for these groups to pursue further research and support.

What are your favorite success stories and learnings from the GeniE pilot?

SB: The first is our partnership with the TANGO2 Research Foundation. TANGO2-related disease is a rare genetic disorder caused by pathogenic variants in the TANGO2 gene. That’s the first gene that we piloted with GeniE.

We discovered a pathogenic variant more common in individuals with an admixed American genetic ancestry, including Native North American, Central American, and Hispanic ancestries.

This finding was particularly interesting because Dr. Seema Lelani, a physician-scientist at Baylor College of Medicine and board member of the TANGO2 research foundation, was the only physician who had seen patients with this variant at the time of the collaboration. She noted that many of her patients were of Mexican or Mexican-American ancestry, reinforcing our data suggesting a higher prevalence in this population. This led the foundation to strengthen collaborations in Mexico to improve diagnosis. Within three weeks, they conducted educational seminars with physicians in Mexico and developed Spanish-language literature on the disease. They also used the data to secure funding to provide more services to patients along the Mexico-Texas border.

Another success story is our partnership with the Association for Creatine Deficiencies (ACD). They focus on early diagnosis and research for treatments of cerebral creatine deficiency syndromes. One of their genes, guanidinoacetate methyltransferase deficiency (GAMT), showed a lower-than-expected prevalence based on unpublished data ACD had access to. We reviewed the possible reasons for the underestimate, including needing a bigger sample size for population data and continuing to update the list of known disease-causing variants.

A year later, ACD Executive Director Heidi Wallis set up a meeting between our team and ClinGen’s Cerebral Creatine Deficiency Syndromes Variant Curation Expert Panel (VCEP). They had recently finished reassessing many of the variants in GAMT and updating their classification guidelines. We all wanted to know how this new data would impact the genetic prevalence estimates. When the new variant data was integrated into the analysis, the prevalence numbers increased, demonstrating the evolving nature of genetic data and the importance of collaboration across multiple groups. GeniE played a crucial role by enabling us to quickly replicate and update findings as new data emerged, highlighting the tool’s ability to adapt and improve.

Read more: Charles Drew University Takes Steps To Increase Diversity in Genetic Counseling Workforce

What is the next phase of GeniE now that it has fully launched? How do you anticipate it will benefit patient communities?

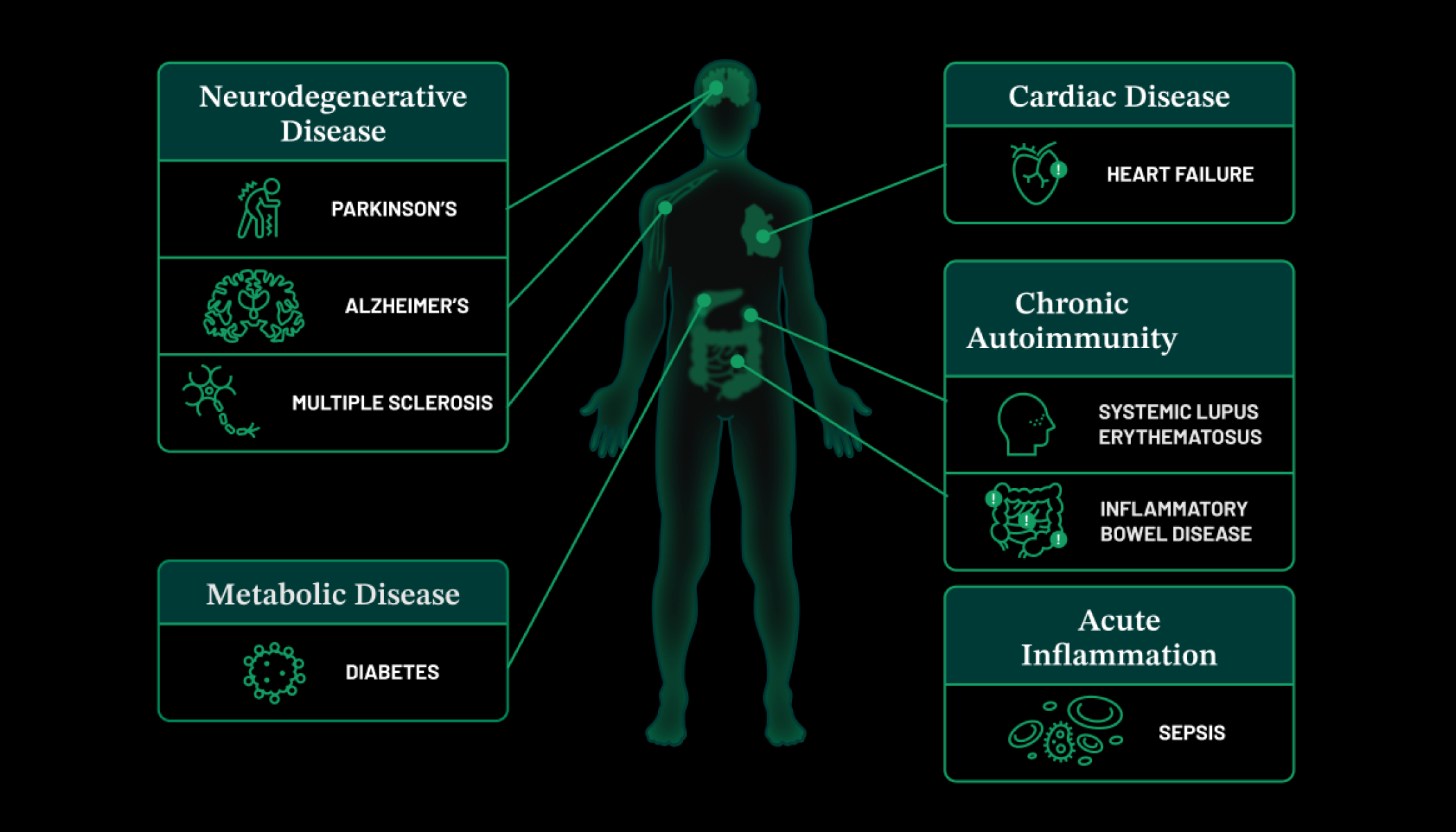

SB: Now that GeniE has fully launched, we’re focusing on expanding its capabilities. So far, we’ve concentrated on recessive disorders, but the next phase involves moving into autosomal-dominant and X-linked conditions. These genetic disorders present challenges and require unique approaches, but we’re committed to tackling them. I hope that over the next year, we’ll have autosomal-dominant estimates integrated into GeniE.

Another critical goal is to encourage more groups to engage with GeniE and provide feedback. The tool has grown significantly thanks to input from patient communities and other organizations, but the more feedback we receive, the more user-friendly and effective it can become. It’s all about making genetic data and its implications more accessible and understandable to everyone.

Ultimately, we aim to foster open conversations and enhance accessibility, ensuring patient communities have the tools and knowledge to advocate for and participate in research. By continually improving GeniE based on user feedback, we can better support these communities in their quest for diagnosis, understanding, and potential treatments.