PART 1

It’s December 7, 2007, and I am being admitted to the Emergency Department of a large Southern California hospital. This time, at least, wasn’t because of a 911 call with my husband coming home to find me unconscious and unresponsive. By now, we’ve learned the signs that my breathing is taking a dangerous turn, but we’re still woefully ignorant about what’s going on with my health.

I’d been diagnosed with an unspecified neuromuscular condition shortly after birth, but the apparent rarity of my disorder and the lack of a specific diagnosis meant that the clinicians I’d encountered had no experience in treating it.

I have respiratory failure. I have pneumonia. I likely have a collapsed lung. I’ve averaged only 2-4 hours of interrupted sleep a night over the past several weeks. My breathing function is somewhere under 30% of normal. My end tidal carbon dioxide is measured at double the expected value. My body temperature is in the 80’s. I’m fading in and out — one minute I’m somewhat coherently answering the medical staff’s questions who are trying to get history and vitals — and then the next, I’m unconscious, though I don’t realize it’s happening. And while this is all pretty extraordinary — my husband has been through it twice before, and he just picks up answering their questions where I leave off. “This is the third time we’re coming to the ER, he says. They admit her, she sleeps for a few days with a breathing tube, and then they just send us home with oxygen. But I think the oxygen is making her worse, not better. She talks and she makes no sense. She’s so tired all the time. We started pointing a fan at her face at night, that seems to help a little, he tells the doctors.” They are stunned that I’m any kind of coherent with such a high CO2, and continue to bring more clinicians in to share and discuss my case. We’re both worried, my husband more than me because high CO2 really does a number on one’s danger-sense — everything starts to feel just fine.

We’re both thinking — is this it? I’m 10 years older than doctors predicted I’d survive. I’m supposed to eventually die of some sort of breathing complication, so I guess here we are. There’s a lot unspoken going on between my husband and I — when I’m conscious — and we’ve just about given up hope that there’s going to be a way out of this. We’ve been building to this for quite a while. And 10 years past my supposed expiration date — well, you just start normalizing it.

I go for a chest x-ray, they confirm the pneumonia, but not a collapsed lung, thank goodness. They say it’s going to take a couple of hours to admit me to the ICU. The plan is to intubate me — which is when they stick a tube down your throat to help you breathe, start antibiotics, and sedate me to give my body time to reverse these alarming stats. We settle in to wait, my husband gripping my hand uncomfortably, but I don’t complain.

Another physician working that day overhears, Adult female with an unspecified muscular dystrophy…” and it piques her curiosity because she has an affected child of her own. She asks her colleagues about my status and history, and then introduces herself as Dr. Anna Rutkowski. She asks some questions, and permission to do a cursory examination. Proximal weakness, check. Joint contractures and distal hyperlaxity (otherwise known as bendy fingers), check. Red, bumpy patches of skin called hyperkeratosis pilaris, check. Respiratory insufficiency, check. She tells us that she needs to look in on her cases and try to verify some of her suspicions, but she would be back soon. Her attitude is oddly cheerful, leaving my husband and I a bit speechless, particularly amid our coming to terms with the fact that this was the beginning of the end.

About a half hour later, Dr. Rutkowski returned with several printed pages and said, “I think you have Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy or Bethlem myopathy, but I’m guessing you’re somewhere in the middle of those phenotypes. We will of course need to verify our suspicions with genetic testing, but I’d be surprised if we’re wrong.”

She had emailed a researcher with whom she had recently become acquainted, in her quest to find answers for her daughter. He directed her to a recent publication characterizing the spectrum of neuromuscular disorders called Collagen 6-related congenital muscular dystrophy. My husband and I are shocked, overwhelmed, and not at all sure of what to make of this chance meeting, but for the first time in my life, there is something — someone who seems to know more than I do.

I was finally admitted to the ICU, and over the next seven weeks, I was in fact, intubated, treated for pneumonia, given a PICC line because I couldn’t maintain an IV, given 4 liters of whole blood for anemia, and treated for an eventual collapsed lung. I spend Christmas, New Year’s, my husband’s birthday, and our 5th wedding anniversary in and out of consciousness and on a feeding tube. My teeth weren’t brushed and my hair wasn’t washed for nearly all of that time. My husband spent 18+ hours a day by my side, only going home to rest, shower, and check in at work. He tried to keep me entertained — we had audio books and magazines, and we pretended like this was all going to be fine and I’d be home in a few days. It’s a really dark time for me, psychologically, especially when he heads home for a few hours and I’m alone. I do everything I can not to cry when he gets up to leave so he doesn’t feel guilty. But he knows. And we both know that this is not sustainable for him — that maintaining this schedule is destroying his health too.

I try multiple overnight trials on noninvasive ventilation, or BiPAP, but they were unsuccessful. The mask makes me terribly claustrophobic, and my weak and fatigued breathing muscles can’t exhale past the incoming air from the breathing machine — so I’m in this constant state of panic because I can’t ever catch my breath until they take me off it and let me go back to breathing with the tube down my throat.

One morning, after being up all night yet again, miserably and futilely trying to learn to breathe with BiPAP, my husband had headed home for a few hours as usual. A resident barges into my room, all but yelling at me with pretty shocking hostility. She says that since I don’t seem to be trying hard enough on BiPAP, I need to authorize a tracheostomy, or I was choosing to die. Imagine, being intubated — which meant I couldn’t talk — sleep deprived, anemic and on pain medication, all having a terrible impact on my decision-making capacity, and I’m presented with this impossible ultimatum, my husband not there to interrogate this apparently urgent decision. “It’s Friday,” she says, “the surgeon’s leaving for the weekend in less than an hour SO THERE’S NO TIME if you expect us to save you.

I’m frantically trying to write out questions on my note pad, but she’s not interested. She’s got a consent form for me to sign. She even insists that I use her pen. I’m so tired, so incredibly vulnerable —ambushed while my husband is gone. My mom had raised me to be a pretty good self-advocate — but I’ve got nothing now. I scribble on the notepad again – begging her to reach out to the doctor I had met in the ED who seemed to know something about my condition — but she ignores me and keeps pressing for me to sign the form. She literally POINTS AT HER WATCH and pushes the document in front of me. Terrified, in tears, feeling like I have no choice if I want to live, I sign the form.

My husband returns a little while later to find me in total panic, and the staff preparing me for the tracheostomy. I’m barely able to convey what happened. He tries to ask questions, but he, too, is met with the attitude of we are the doctors, you will do what we say.

So they perform the tracheostomy right there in my room. They put me under with propofol for all of twenty minutes. When I come to, I’m terribly sore, groggy, and angry. “This doesn’t have to be permanent,” my husband tells me. Let’s just get you well and get out of here.”

I’m told that I will likely never be able to speak or eat anything substantial by mouth again, and that even though this tracheostomy has saved my life for now, my prognosis is guarded at best. Patients with tracheostomies, I’m told, are considered “end of life”, with little hope of ever going back to normal.

So a little over a week later, I’m regaining some of my old self. My husband is so happy to see me alert and animated in a way he hadn’t for more than a year. I decide to start trying to catch up with work, even hosting a couple of meetings with colleagues from my ICU bed — still unable to speak — or rather not realizing I should try — but getting really good at writing in my notepad and gesturing, while my husband is learning to read my lips. I’ve always been good at adapting the environment to serve my needs, so I’m thinking, Ok, maybe I can do this, maybe I can go back to some semblance of normal. Maybe I can go home at some point.

And then I’m handed some pamphlets for nursing homes, and told I need to pick one by the end of the day because they need my ICU bed.

After almost two months in the ICU, I’m transferred to a subacute facility to continue getting better, and then … we’ll see. I learn how to breathe without the ventilator while awake. I figure out that I actually can eat, and even talk, also while off the ventilator. They tell me I can start thinking about going home, as long as I work with a home health company for the transition and delivery of a home ventilator. My discharge date ultimately gets postponed by almost two weeks because the nurse, in trialing me on the ventilator I was to take home, pushes a button on the machine that delivers such a large volume of air that my lung collapses again.

The transition to home was rocky, but we get through it. I’d lost an incredible amount of strength and motor function lying in a bed for most of the winter, and my joint contractures had worsened. But I was getting just a little bit back every day, enough to give my husband and I some hope. We bought a new bed that could be adjusted like the one at the hospital does, and settled into something not quite normal, but certainly leagues better to just finally be home.

Every medical professional we encountered continued to be completely at a loss at how to handle my care. I wasn’t opposed to figuring it out, but I was perplexed as to why this was all such a mystery to everyone. We had to learn a whole new regimen to take care of my tracheostomy, and quickly discovered that at $800 a month to rent this ventilator, we’d be better off trying to buy one.

A few weeks after coming home, what felt like a lifetime ago, that ER doctor I’d met, Anna Rutkowski, invites us to breakfast, and we get to meet her affected daughter and husband. Sitting in a small cafe, she scribbles out a picture of the structure of muscle cells on a napkin, explaining how the various building blocks of muscle are all interdependent — and how failure in any of those building blocks can happen as a result of genetic mutations — mutations that cause one of dozens of neuromuscular conditions.

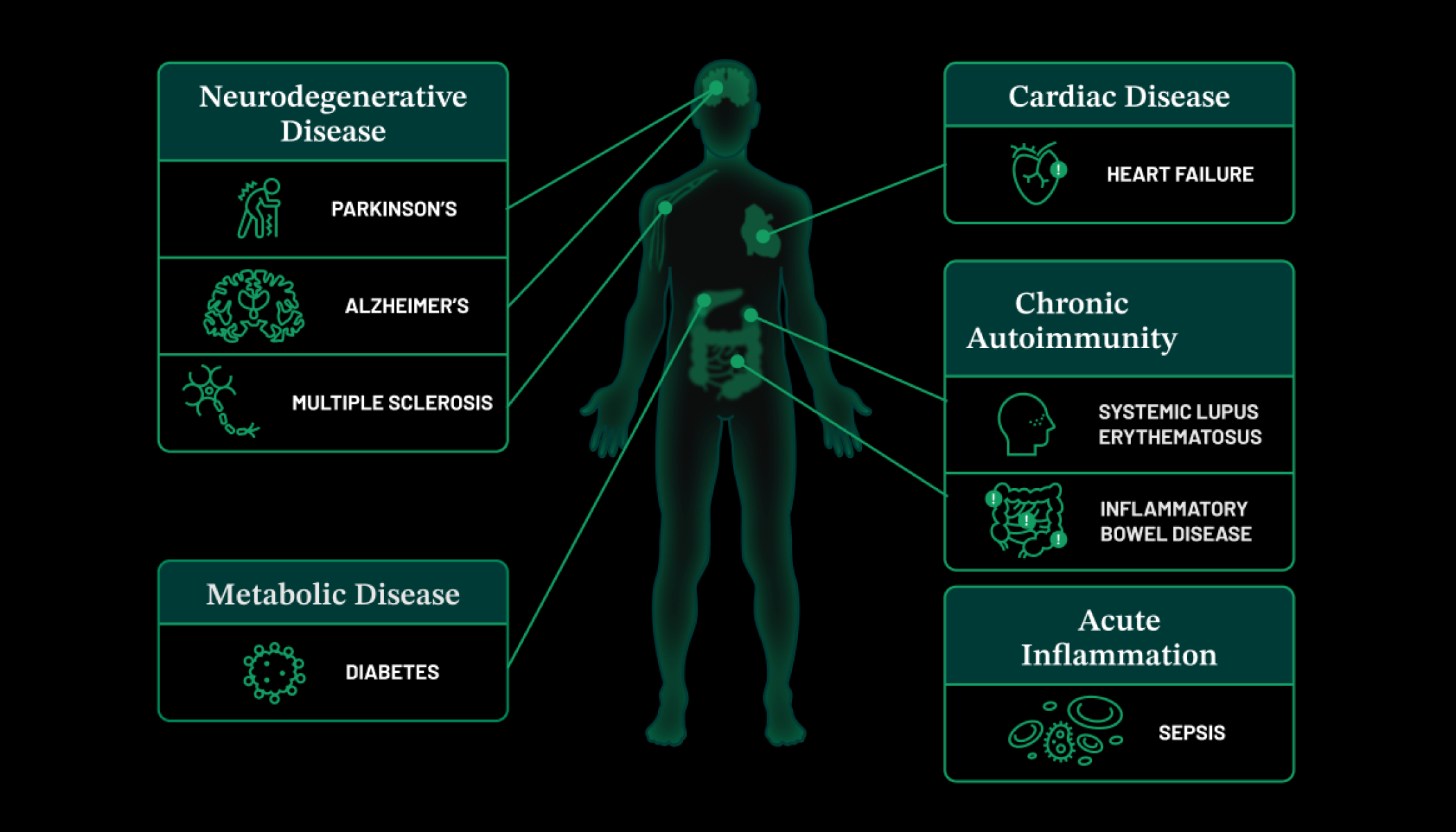

She shares plans for a new nonprofit that she and two other parents would launch, to be called Cure CMD, focused on finding treatments and a cure for the five primary subtypes of congenital muscular dystrophy. Her enthusiasm and confidence that we could eventually solve all of this was infectious, and I started volunteering for this fledgling organization. Four years later, I was hired as its first employee. Anna arranged for me to get genetic testing, and it turns out, her suspicions were correct — I have Collagen 6-related congenital muscular dystrophy. It’s ultra-rare, so I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that no one I’d encountered up until that point had a clue what to do with me.

In the first four years following Cure CMD’s incorporation in 2008, it was an all-volunteer organization, run largely by parents, grandparents, and spouses – all of whom had jobs and loved ones with profound disabilities to care for. We fund our first research project. We start a patient registry. We convene the first congress to develop standards of care. We partner with an amazing team from the National Institutes of Health to travel around the world, teaching local clinicians how to recognize and diagnose the various forms of congenital muscle disorders. And we host the very first scientific meeting dedicated solely to congenital muscular dystrophy. All the while, families living in siloes with unanswered questions, with care providers ill-equipped to manage these ultra-rare conditions — families who had never met another person with CMD — people like me — were coming out of the woodwork.

Now as the executive director for Cure CMD, I’ve become a lay expert about not only my own disorder, but the other CMD subtypes as well, and it’s become critically important to me to help educate affected individuals and their families about getting a genetic diagnosis, and the need for proactive pulmonary care. It turns out, ventilatory support, not oxygen, is what I needed before it became life-threatening, and untreated respiratory failure is the primary cause of hospitalization and death for people with neuromuscular disorders.

I continue to defy my “expiration date”, having turned 52 last September, but it’s always in the back of my mind: will today be my last day? But I will never again be in that desperate place of ignorance, and I’m doing everything I can to make sure no one else in my community is either.

PART 2

In my 20s, once or twice a year, I would drive with my girlfriend Angela for over an hour to reach the best neurology clinic in Sydney. Angela would drop me off in front of the hospital to find parking because a hospital probably is the only place that people with mobility issues outnumber those that are able‑bodied.

On the rare occasion that we would find that coveted handicap spot in front of the hospital, we would get the dirtiest look from everyone when stepping out of the car. There is a bias that handicapped people should look a particular way and be a particular age. I would try my best to walk as slowly as possible as not to increase the further suspicion of onlookers passing by. Ironically, it’s actually less stressful to not take the handicap spot than have everyone stare at you when you exit the car.

I still had the ability to walk to the clinic but I was no longer confident. Those with muscular dystrophy fortunate to be still walking do so awkwardly with a gait and usually off balance with each step. For me, some would say it looks like I’m humping the air in front of me. And at night, many just conclude that I had too much to drink.

However, I was at the hospital so it wasn’t a place to be embarrassed about my non‑trendy walking style. It was more that I feared losing balance due to unforeseen obstacles or slippery surface and then falling over. I could no longer get up off the ground myself.

As a young adult, I dreaded asking for help of strangers. And when strangers do help, they don’t first ask exactly how they could help but rush in and just grab random body parts to get me back up. I do love their enthusiasm and willingness to help out, but doing this for people living with muscle dystrophy can cause further injury.

When Angela and I would finally get to the clinic waiting room well before time, we would of course be told that the clinic’s running late. It’s usually one to two hours late by that time. No hope for me to go to work afterwards and have a productive day.

The waiting room was always extremely crowded as others would travel with their families to this clinic. Fortunately, there would be a few seats left, but this required me to walk around obstacles and avoid feet and other things to get a seat.

There usually wasn’t two seats next to each other. This was before smartphones and women’s magazines were just not my thing. I usually had to sit in boredom by myself to be left with my thoughts.

As a naive young adult, I was always hopeful that the neurologists would say something like, “There has been a medical breakthrough for your condition and here is the drug that will make your muscles stronger.” Or, before I got my clinical diagnosis of muscular dystrophy, that they had made a mistake and I had a condition that can be reversed with a special diet. This was definitely possible, particularly before they took a muscle biopsy from me. It was the hope that they would look at the biopsy and say, “Wow, it looks like things are fine, so it must be something else.”

Unfortunately, things were not fine with my muscle biopsy. As a reminder, this was an adult neurology clinic so it was surrounded by patients and families that have been going to this clinic for many, many years. They were not a fun and positive crowd and appeared to be there more out of routine, no longer seeking treatment and hope.

I was fortunate that I was too unobservant to notice and I was stuck in my daydreams of a miracle cure. When it was my turn to visit the neurologist, he would always have a training neurology fellow in the room as it was a university teaching hospital. I was totally cool with that. I just wish I remembered to put on a better pair of underwear as, usually, this involves taking off all my clothes, except my underwear, so it’s always good to have your best.

It would be usually the same set of muscle strength tests, which is quite subjective and required me to push against the neurologist examining me. It would be scored between zero to five, where five was considered normal. My form of muscular dystrophy affected my lower limbs first so I had maintained upper body strength and wanted to prove it to the neurologist who would have been in his 60s.

When examining my arms, I would nearly push him over. I’m not sure why I did it but I just wanted to see if I could score a five for at least something, just to feel normal. Though he would never give me a five. Four‑plus was the best that I could ever score.

After examining me, he would then look at me and pause. I thought he was going to say something profound but would say the obvious, that my muscles were getting weaker and then would wrap up my visit asking me to make an appointment to see him in six months’ time.

At first, it was fine, as I thought perhaps in the next year or so there will be treatments so it would be good for me to go to this clinic so I’m first in line. On some visits, Angela and I would mention scientific publications or news articles we read about muscular dystrophy and treatment. Our neurologist would discuss so as not to be rude, but usually didn’t really care as it was his job to watch me slowly waste away and it was my job to accept that.

He once told me to look after myself and drink a lot of water and try to live the best possible life. Most rare disease patients are told similar things. This made me really angry as it implies that people with disabilities should just settle for whatever they’re given in life. For me, I may be disabled but my dreams and ambitions are certainly not.

It got to a point that I lost patience. For this particular day, I had enough. Imagine having to go through the physical and mental exhaustion, losing a day of annual leave for each visit and then being told something as obvious as your muscles were getting weaker. I don’t want to sound entitled but rare disease patients deserve better from their healthcare provider and for them to empathize what we are going through.

Yes, some have given up, like many of the adult patients in the waiting room, but I was young, naive and stupid. I wanted to do something about it.

After leaving the neurology clinic that day, I told Angela that I wanted to become a medical researcher to work on muscle diseases. She was extremely supportive and could understand as she was there for every neurology visit.

Unfortunately, others in my life were not as supportive. The training neurologists pulled us aside and said condescendingly to us, “Leave it to the experts.” But I wasn’t satisfied. The experts were telling us the bloody obvious, that my muscles were getting weaker and nothing else.

Ironically, this actually made me want to pursue a career in research even more just to prove him wrong. During that time, I had earned two additional bachelor’s degrees, a PhD. But, with that, a lot of setbacks in terms of financial setbacks and also being really out of my comfort zone, living cities that I didn’t see myself living in, such as Boston, which was a really difficult city for a handicapped person to navigate.

But having said that, I did make a lucky set of decisions and also was at the right place at the right time by putting myself out there. On January the 2nd 2018, I woke up to my first day of being a Yale professor. As a student, I would have been intimidated to meet a Yale professor and, now, I’m that guy.

I was given a research laboratory that could fit eight Ivy League scientists, but when I counted, I looked and it could actually fit 16 non‑entitled scientists in that space. I finally made it to the pinnacle of science as I was given a laboratory to fill with my own team of scientists to pursue research that was important to me. I could change the world in terms of rare disease research, make new disease gene discoveries and develop therapies.

However, my biggest challenge on that day was how do I get from Point A to Point B on a snowy New England day without getting hurt. It may sound trivial, but not to those with disabilities.

January is winter in New England and that means there is usually a lot of snow. I had only moved into my new house in Connecticut a few days before starting so things were not perfect in terms of accessibility. I was now 38 and my disability was a lot worse than when I was in my 20s. I could no longer walk without a stick, struggle to get off a chair and it was almost impossible for me to get off the ground after falling.

There were three steps to the house and no railing. For those that don’t know, this is Mount Everest to people with physical disabilities. However, I had found a way to navigate this challenge by parking the car close to the steps and using the door itself as a railing and using Angela, now my wife, as the person I could lean on the other side.

The streets around Yale had been plowed that morning. Plowing is when a large truck pushes all the snow on the street off to the side. It normally piles up on the curb and can sometimes be a few feet high. I always wondered what happened to a pile of snow during winter. I soon realized nothing. It just sits there and then becomes gray, but it’s the yellow stuff that I was told to avoid.

I didn’t have parking on the first day despite organizing weeks in advance to have parking in the lot closest to my research lab, so we had to drive around, find a suitable place for me to get off. I was looking for a gap between parked cars that didn’t require me to jump over a pile of snow besides the curb.

We finally found a spot. I stepped out of the car and onto the street that was all slush, which is a mix of snow, ice and mud. My first step away from the car, my feet just slid and I now no longer have the strength to stop it. I fell straight onto my bum in an epic mess on the ground.

My bum was totally drenched but I wanted to get up as quickly as possible so as not to be spotted by anyone that would soon get to know me. It’s embarrassing that I could be a leader in research and I couldn’t even cross the road by myself.

Once I finally got into the research building on the medical campus, I no longer wanted to do research. I wanted to do something about my transport situation so I wouldn’t be embarrassed again.

I went over the transport office. I was so furious I didn’t care that I had this big, wet patch on my bum and everyone could see it. The line was really long that day. I guess everyone dreaded taking public transport in the winter.

When I finally got served, I told them that I was disabled and required parking and I had been trying for weeks. They told me to wait for the permit to be sent in the mail even after I told them about the epic fall.

It made no sense. So, all these able‑bodied people in the line should get their parking before me. I refused to step away so they eventually asked for my ID badge.

It was really odd. When the woman serving me came back and said to me, “Sorry, sir. Let me organize your parking,” and then came back with my parking permit sticker and my ID badge was enabled.

It took me a while to register just what had happened. It finally clicked that the reason why I got my parking on the spot was due to my title of professor and not my need as a disabled individual. I thought, “Cool, I can use this title to complain and finally get some of the things that handicapped people require in the workplace,” as my dry Aussie humor load was only going to get me so many things in life and use my research to help others.