PART 1: DONNA APPELL

My husband and I planned everything. We worked really hard helping each other through school and finish our education. Finally, it’s time to plan our family.

Our daughter Ashley was born and she was the talk of the nursery. My husband was born in Malta so he has Mediterranean coloring, and my hair color comes out of a bottle.

Ashley had this unusually full head of white hair. It took a little bit to get past that it-must-have-been-the-milkman comments but I watched everybody looking at her in amazement. I was so proud. I saw strangers at the nursery window look at her.

When we went home, we wanted to bring her to meet the family. She was two weeks old and, to travel, we needed a pediatrician’s clearance, like a well-baby visit. The doctor checked Ashley and then left the room and came back with a book showing me animals and strange-looking people with albinism and told us our daughter would not be able to see. That was on Christmas Eve.

We cried over the idea that our daughter didn’t have normal vision. She was legally blind. The first thing you think about is, “Well, she’s not going to be able to be an astronaut,” and that’s kind of a stupid thing to think because how many people really are astronauts? But then I started to think, “She’ll never be able to drive,” or, “How well will she do in school?”

From there, our special baby had difficulty growing. When she was a toddler and tried to start to walk, I noticed that she had little bruises on her shins and I couldn’t figure out where they came from since she was only experimenting on the living room carpeted floor. Why would she get bruises?

I brought it to the pediatrician four times and got the stupidest explanations, like, “Her skin is fair so you see bruises more.” I thought that was ridiculous because you either have a bruise or you don’t have a bruise. It really doesn’t matter what color your skin is.

I was desperate for answers so I started to read and investigate on my own. And I read this sentence in a booklet on albinism that talked about a rare bleeding disorder caused by a platelet defect in some types of albinism. I guess wanting to protect my daughter so much, I was fueled to call this author of this pamphlet.

I got him on the phone and explained the issue and he sent me a test tube in the mail so that we could draw Ashley’s blood and send it back to him. That was three time zones away. So much for finding answers in New York.

In a week or so he called and told us that she had Hemansky-Pudlak syndrome or HPS because of the way her platelets looked under an electron microscope. I was totally shocked and ready to pack up and move to Minnesota just to be near the expert that finally responded to my concerns.

He told me to stay put, learn the disorder, teach the caregivers, teach her doctors, create experts.

“Holy crap,” I thought, “I have to teach doctors about her disease?” That was a tremendously frightening notion.

He went further to explain that it should be okay. Nothing too terrible. It should be albinism, which is fair skin, legal blindness and an added mild bleeding disorder. Go procreate. Have more children with no fear, he guided us.

His words satisfied us. Ashley was growing a bit slowly but she was active, inquisitive, happy, delightful. And she was absolutely thrilled with her baby brother Richie who she came to name Broccoli.

When Ashley was two months short of three years old, that night would change our lives forever. It was October 12th at 3:00 in the morning that I heard her whimpering in her crib. I went into her room and I saw her diaper was full of blood. It was all over the sheets.

I panicked and I knew I had to get her to the hospital, but my instincts made me clean her diaper first. Terrified, I watched that diaper fill and I couldn’t get her clean. It wouldn’t stop coming.

I wanted to get her to the big hospital not where the ambulance would take her. When I got there, they took Ashley out of my arms, took her to an intensive care unit and by the time I saw her again, she was filled with IVs and monitors and lines. I could hardly recognize my own daughter. Our terror was indescribable as we prayed that she would survive.

We were in the hospital for about three months. She had 36 units of platelets, six units of blood before they ever stopped the bleeding from her bowel disease. And because of all that blood loss, she sustained a traumatic brain injury from the lack of oxygen to her head. So much for a mild bleeding disorder.

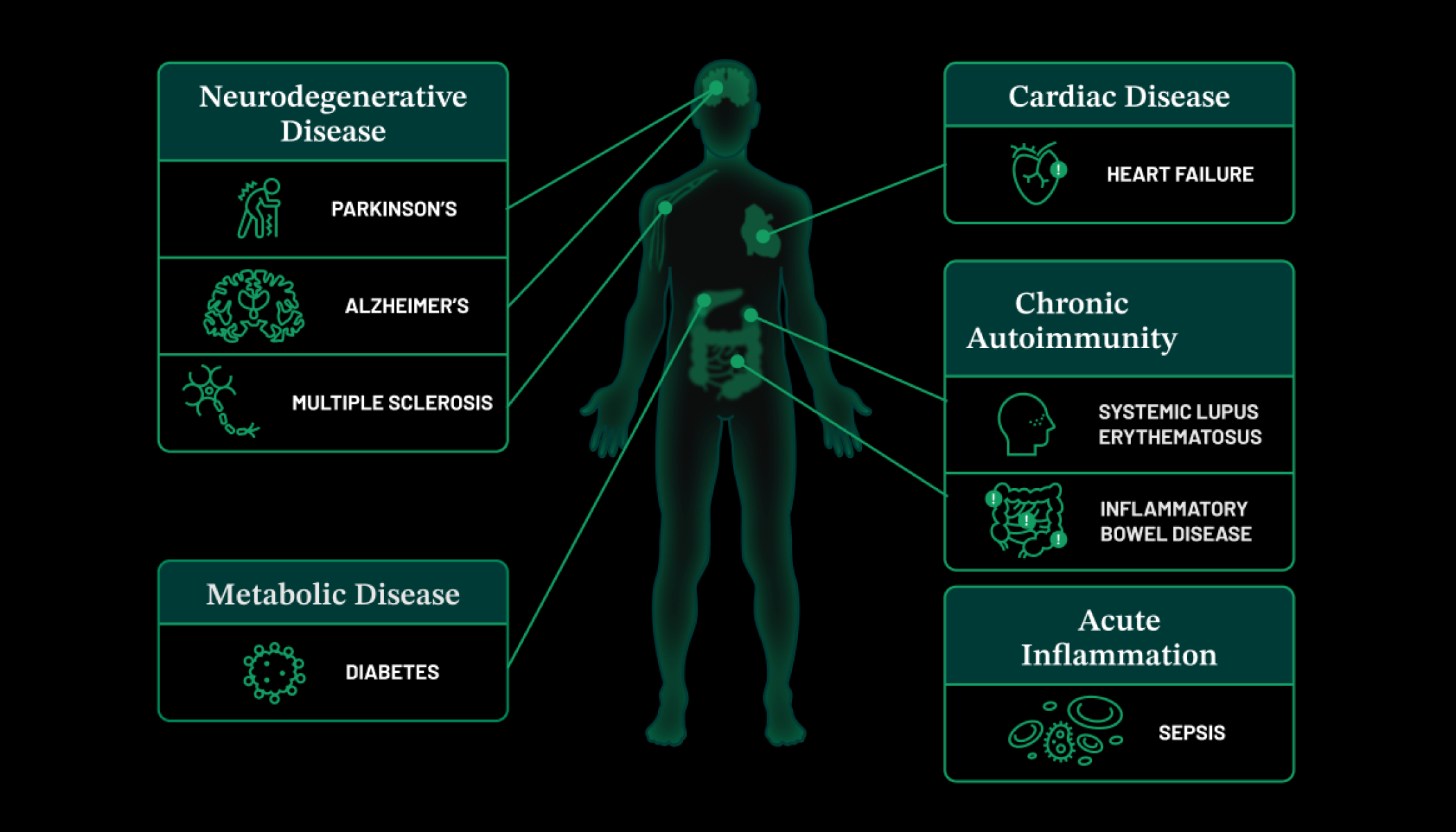

We subsequently learned that HPS is not just albinism, legal blindness and a bleeding disorder, but it could involve this colitis and a fatal lung disease that would significantly shorten my daughter’s life.

The first thing we did was to try to find other families that had this. We looked for researchers and research. I tried to find treatments, look for a cure. I found nothing.

So my husband and I thought about it and we decided to start the Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome Network because we couldn’t imagine any other family being so isolated. We started putting our names in little directories and we began to slowly collect family stories. We opened our home for the first conferences that we had and we actually got the attention of a brilliant NIH researcher from a cold call.

To help find the gene, we collected blood samples of DNA in our basement. My girlfriend came and drew blood. We were also asked to get two bottles of 24-hour urine buckets from each person, and by the time we were done we had collected about a dozen. These bottles and jugs had to be refrigerated so we had to plan this event in January so that we could keep the urine buckets on our deck in the snow.

I remembered back to the diagnosing doctor’s myths before she hemorrhaged about how this was a mild bleeding disorder, but he also mentioned that it was because we were not of Puerto Rican descent, and I started to think about that. So I started to research and investigate what is going on in Puerto Rico.

What I found was HPS has a founder’s effect on the island. A founder’s effect can arise from a cultural isolation issue, like an island surrounded by water such as Puerto Rico. Over many, many decades there becomes a genetic drift that includes the genetic defect in the original descendants.

Founder’s effects occur in many genetic disorders. For instance, people think that sickle cell is only in African-American people or cystic fibrosis in Caucasian people or Tay-Sachs in Jewish people. Though it’s really frequently in those nationalities, it still occurs in all other nations.

Anyway, due to this founder’s effect on Puerto Rico, there are a lot of people with HPS there, and they are dying. They develop a lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, that scars their lungs and stop them from having the ability to expand and contract. Literally, they slowly suffocate. This begins to happen to people with HPS type that’s very frequent and it happens in their early adulthood.

Learning about this, my husband and I decided to get on a plane and go down to Puerto Rico. We wanted to find what was going on. We spent the first week going door to door in neighborhoods, visiting families. In Puerto Rico, they live in the same neighborhoods. On the mainland, we weren’t even in the same states. We saw so many people. It was incredible.

I remember meeting this lovely family with three small children with HPS. It was an adorable house. Very colorful. With terra cotta floors and the coverings of the windows, there were window coverings which I really was happy about since I saw so many people having sunburns and skin cancer from constant sun exposure.

There was a small TV in the room and I saw the three children trying to sit directly in front of the TV. Each one was trying to be able to see it better. I don’t think anyone had a very good advantage. I really don’t think any of them saw it very well.

But when I spoke to the parents, they told me that they had understood that HPS was carried one in four. That means that there’s a 25% chance that they have a child with HPS with each conception. What they thought it meant was if they had one child with HPS, the next three would be fine. My heart broke when I thought about how many other people on the island didn’t understand the genetics.

Down the block, I visited a family whose dad worked in a coumadin factory. Coumadin is a drug that is a really strong anticoagulant. He wondered that if he came home at the end of the day and he was covered with coumadin powder, was it okay that his daughter with HPS would run up and give him a big hug.

I was overwhelmed with the amount of education that needed to be given on the island. I felt helpless. I was a stranger in their homes. I didn’t remember a morsel of my high school Spanish. Even though I used interpreters, they couldn’t communicate how much I desired to help them.

Remembering the comment from our first doctor about creating experts, that came back to haunt me. And it was daunting because we were on an island that I had never been to before.

But my husband and I beelined to a pulmonologist that was given as a recommendation that people respected. I asked him what inhalers are being prescribed and when did these folks go on oxygen. His answer was that there’s no need to treat them because they’re going to die anyway. I felt sick. He was talking about my daughter too.

From that moment on I knew I had to try to make a difference. I had to stop worrying about the language barrier and I had to speak from my heart. My daughter had the same gene as their children and, as parents, we all speak with the same language. For me, with tears.

We need a cure. So for the next two decades, we spent working together to help with the quality of care and access to it. It took a long time to develop strategies and rapport there, but last week our amazing team were responsible for enrolling 44 individuals with HPS into a multi‑disciplinary comprehensive care clinic.

We annually host conferences there for families in Puerto Rico and we also provide accredited medical education credits for the doctors and physicians and clinicians.

We offer genetic testing, transportation to our meetings. In the past we’ve sent buses around the island to pick everyone up because they can’t drive.

We are creating experts, both clinicians and families. And most importantly, we’re creating access to them. It’s not just me and Ash anymore. It’s over a thousand families, incredible physicians, researchers, an amazing board and leadership team. We’re all trying to help to change the course of this disease.

We still don’t have a treatment. We’ve lost a generation of members, but we work really, really hard.

For Ashley, I thought that we would have enough time to find help for her, but time’s passing. Again, we don’t have a treatment. Living inside this organization she has had to witness over and over again her friends with HPS dying. While most might despair, I am constantly amazed by her resilience. Because now she works right beside me trying to help the HPS community, trying to find a cure with every breath.

PART 2: JENN PERRY

It’s 2010 and I’ve just been diagnosed with Li-Fraumeni syndrome. And LFS, if you haven’t heard of it before, is a rare syndrome that predisposes people to multiple forms of unrelated cancer. It’s a really tough diagnosis, I find, because it’s not just dealing with the individual. I actually have to live with the guilt of passing this on to my two daughters.

My sister also has it and I think what’s really devastating about this syndrome is that, like I mentioned, it doesn’t just affect the individual but really families as a whole. Generations, if you will. It was really a very tough diagnosis to be hearing.

It’s been three months since my younger sister Stephanie and I have been diagnosed and it’s really scary. My mom has passed from cancer as well as several other family members and it doesn’t feel real. But I will say that the pieces are starting to come together of that family puzzle, because we’ve always felt like we’ve been cursed. There’s been so many family members that have had cancer in our family. So although it’s not the diagnosis I want to hear, at least it’s beginning to answer some questions.

As I’m reeling from this news, I get this invitation for the first ever LFS conference from my doctor. I really want to learn about it, but as I mentioned a little bit ago, it is very scary.

My sisters and I, my older sister Debbie and my sister Stephanie, who’s my younger sister, really discuss what do we do. Should we go down to this conference? We talk about how there’s only 565 families in the whole world. That just really kind of blew my mind but that’s how rare it is. In the whole world there’s only 565 families.

So we feel, in the end, it’s a really great opportunity to hear from the experts, to learn a lot more, a little bit more, something about this rare syndrome. And we feel that it’s best for our families.

I am very grateful, though, my older sister does not have LFS. But, in the end, the three of us decide to go. As we always have, we’ve stuck together since my mom passed away.

So we head down to Maryland to go to this conference. We’re hoping to meet other people, like I said, and get some answers. We haven’t been away very much as three sisters so we’re kind of excited as we’re traveling down there. We have some light conversations and what are we going to experience and talk about all these types of things.

But as we take the cab over to the NIH, the National Institute for Health where the conference is being held and we’re walking up the sidewalk, getting ready to enter the door, I’m finding it really difficult to get into the conversations. I kind of laugh. I call my older sister Debbie ‘People Magazine’. I’ve never seen anyone so curious about everyone’s business and what’s going on. She’s very in tune with that.

But as my two sisters are talking, I really find myself very numb and I don’t even hear what they’re saying at this point. As we walk through the door, that’s kind of how I’m feeling. If that isn’t hard enough, we then enter this large auditorium and there’s hundreds of people sitting there.

The good news is I see my doctor right away with a friendly smile and that puts me at ease a little bit. We say hello and she ushers us pretty quickly right up into where we’re sitting.

It’s amazing to hear all the things of what’s going to happen. As the scientists and the doctors start to speak, I have to tell you it’s like hearing several different foreign languages. These terms and phrases that we don’t even understand are being told to us. We understand bits and pieces but even that is quite the education.

Thankfully, just as I’m beginning to get overwhelmed in the moment of what’s happening during this conference, they sent us on break which was quite the blessing. As we’re going on break, what do we decide to do? We open up our books with all the notes that we’re taking and we’re Googling terms on our phone and trying to understand everything that’s just been said to us.

As we’re doing this, I noticed there’s a few gentlemen sitting in front of us and they’re staring at us. They’ve turned around and stared at us and are looking at us. One of them, I consider him the bravest, turns and really says to us, “Are you patients?”

We look at each other, the three of us, the sisters and I and we say yes. They begin to explain that they all are researchers and scientists in the field of LFS and they spend all day long looking under a microscope trying to study this syndrome and understand it and try to find the cure. They are just so inspired and so motivated to actually meet people, in other words faces to this syndrome, and that this is going to inspire them to even do more work as they go back into their research labs.

It was just very impressive to me because I began to realize that at this point my perspective starts to change a little bit. Just as I was so afraid and so numb, I start to get this small feeling and it’s actually a good feeling. It’s no longer such doom-and-gloom for me all of a sudden. Just a small bit of hope kind of really begins to form inside of me. I realize I’m not so powerless. That even though I’m not a doctor or scientist, I might be able to make a difference even though I’m not a professional.

So points throughout the conference, they put us in these breakout rooms, these small breakout rooms with different— all the patients gathered. None of the doctors. None of the scientists or researchers. Quite honestly, we don’t like being separated. Call us crazy but we’re like sponges now at this point.

Suddenly, I’ve become this addict for this information, the information I didn’t want to hear at first. I don’t really expect this but I really can’t wait to hear the next speaker. I’m waiting for this big revelation. I think everyone in that room in terms of us all of us patients are hoping that, by the end of this conference, we’re going to have some great answers, some solutions.

Unfortunately, as I quickly realize, my prayers are not going to be answered in this way. But as I continue to learn, I realize a new me is really starting to come out and that makes me a little bit more confident.

The conference comes to a close and what they do is they put us in this large auditorium, all together all at once. There’s probably a hundred of us there. We notice at the front of the room, all gather around one podium, if you can believe it. It’s a bunch of professionals. So there’s genetic counselors, there’s insurance people, all different types of professionals there.

I can tell you for sure what is very interesting to me is the room feels very tense and it’s very serious. It’s kind of like a bomb is going to go off. So I just very quickly but very slowly take a peek around up all the way. I’m towards the front, sitting almost in the front row.

I’m listening to all the discussions that are going on and it’s very interesting to me that people are very serious. There’s a lot of chatter about like, “Why are we here? Why aren’t we in the main room? What do they want to discuss with us here at the very end?”

I think secretly, again, we’re all hoping to get answers but not very hopeful at that point that that’s going to happen based on what we’ve heard.

I do meet this gentleman in front of us. His name is John and he has formed a small group, a virtual forum, if you will, only four or five people. But, again, that’s not really that surprising when there’s not that many people around the world that have this syndrome. But I hear him talking about it and I kind of tune in a little bit.

Then the room gets quiet as they kind of want all of us to pay attention to what they really want to talk to us about. It surprised me but they want to talk about support. Patient support, actually, and how we can support one another. They want us to form some kind of group. They want us to get together. They then ask us to raise our hands. They actually want us to commit to forming this group.

I notice that John, who’s sitting in front of us is the first one to raise his hands, and that doesn’t really surprise me. I know my sister and Debbie and I want to get involved somehow. We don’t know what that means. I can tell you my little sister Stephanie was a little bit too emotional at this point. All three of us are in different places and I can tell you all of us in the room, I think all of us are in different places depending on when we got our diagnosis and where we stand with it.

But I suddenly raise my hand unexpectedly and I can see out of the corner of my eye that my older sister Debbie has raised her hand. Although I’m really nervous, I have to tell you that sense of empowerment continues to build. I’m very excited this time instead of nervous to turn around and see how many people have actually raised their hands. I mean there’s a hundred patients in the room.

So I’m thinking, after hearing all the conversation that started at the beginning, that the majority of people would want to raise their hand. As I look and I start to count, I’m really just shocked that only 12 people out of the 100 that are sitting in that auditorium actually raised their hand. I kind of sat stunned there for a little bit.

But I can tell you at the front of the podium, and I know they all care about us very, very much, but they were greatly relieved that they actually had some volunteers that wanted to form some sort of support group for this rare syndrome.

Three years later, the work of the 12 hands, the volunteers in the room that day, formed the Li‑Fraumeni Syndrome Association. I did become president and I am very proud to say it connects people from all over the world that represent the LFS community, their patients, the families, the friends, all the medical professionals that are involved who have dedicated their lives to the research and care of LFS patients. I do take my job very seriously.

Four years pass and, Holly, my vice president and very dear friend of mine, we have committed to traveling to LFS centers globally and we decide to take our first international trip. These centers of excellence, if you will, are centers that specialize in caring for patients with LFS.

We decide to go to Brazil first because Brazil has the largest contingent of LFS patients in the world. It was amazing to me as we travel down there and we get in front of all of these families and professionals that, now, I’m the one speaking in front of the scores of faces in front of me hoping to inspire them and to help them feel supported.

I scan the audience. I am not speaking very often. This is probably only the second time I’ve really spoken in front of a large group of people and I’m looking at how many people are sitting out there and it seems huge to me. But I get through the speech. I’ve got the PowerPoint slides. I’m guiding myself through this. I think it helps that I don’t speak Portuguese because it took a little bit of pressure off.

But as I’m speaking and I’m getting ready to sit down, I ask anyone if there’s any questions. Quite honestly, I never expect to get any questions. That’s always reserved it seems for the doctors and the scientists and the researchers who can answer some very important questions for them.

But as I pick up my papers and I’m going to sit down, a young man stands up with his wife and they wanted to ask me a question. Kind of took me off guard. But he asked the question and he said do I have LFS.

I don’t know why but it rendered me speechless. I was frozen in time for a moment. I very slowly said yes. I just assumed that everyone knew that I wasn’t a paid employee. I just really thought that people know that when I get up there and speak that I am a patient and I have LFS, but that’s not the case.

And he started to tear up and, to be honest with you, gets me very emotional. That doesn’t happen very often with me but it really touched me. He thanked me and he explained as they are the largest group of LFS patients in the world, there are a lot of people that come to visit them, a lot of researchers and doctors and people who are intrigued and want to learn from everyone in Brazil. But he said I was the very first patient to ever come and speak and visit with them and how much that touched them all there.

That patient-to-patient moment really moved me and stopped me in my tracks. I wasn’t ready for the questions that he asked me. Did I have children? Were they positive for LFS? How did I decide to test them? How do I feel about all the surveillance that an LFS patient has to go through? I wasn’t prepared to answer those questions.

I am not the banner patient. I love desserts. I love to lay out in the sun when I’m not supposed to. I don’t do all the things right that I should as a perfect patient might. I’m really just an average person with this syndrome trying to do the best I can. But this was a very big wake-up call for me, realizing I need to speak more as a patient. Let people see the side of Jenn, not just the organization side.

No matter where I’ve traveled, no matter how many patients are there, one thing that I have realized is that everyone feels very alone and isolated with this rare syndrome, just like me. And that was very important for me to realize.

People ask me all the time why I continue in this volunteer role. It is fast-paced. It changes continually. But, really, my passion is knowing if I can just help one more person, just one more, all of it is worth it. I don’t want patients and their families feeling the way I did as I walked into that door many years ago, to that first conference scared and praying for answers. I want them to know that I’m in their corner and I’m there to help and support them. Nothing is more inspiring than talking in front of a group of people and knowing you have an opportunity to make a difference. Thank you.