Sep 14, 2021 · 21 min read

Betting Big on Science and Technology

Editor’s Note: As of November 15, 2024, Theiagen Global Health Initiative (TGHI) will manage CZ GEN EPI, now renamed TheiaGenEpi. For further information or updates on the tool, please visit theiagenepi.org

Dr. Priscilla Chan, co-founder and co-CEO of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) joined Sarah Neville, global health editor for the Financial Times, at the Financial Times’ Future of American Healthcare Summit for a conversation on how CZI Science is betting on technology to reach our mission to cure, prevent, and manage all disease by the end of the century. Priscilla discussed CZI’s collaborative approach to science and our emphasis on working across traditional disease silos, such as through the Neurodegeneration Challenge Network. Watch a highlight from the full talk, or read the full conversation transcript below.

Sarah Neville: Priscilla, thanks so much for being with us today.

Priscilla Chan: Thanks for having me. I’m delighted to be able to participate.

Sarah Neville: And I gather you’re speaking to us from CZI’s office and it’s actually the first time you’ve set foot in them for 18 months. So it’s a rather momentous day for you.

Priscilla Chan: Yeah, it feels great. It feels great to even behind masks, to be able to see colleagues and say hello in passing and it feels really joyful.

Sarah Neville: Excellent. And could you tell us about how CZI came to be founded? I mean, I think at the center of it all is children, isn’t it? Your own children and other people’s and your sense as a pediatrician that we, as a society, had to do better giving all children the chance to realize their full potential?

Priscilla Chan: Yeah, I guess the first kid in this story is… Or actually my parents, the first kids. I’m the child of Chinese Vietnamese refugees. My grandparents during the war had the bravery and the optimism to put their children on boats into the sea, in the seaside of Saigon and said goodbye because they knew there was a better life somewhere. They knew that there was hope and there was a future for their children and they just didn’t know where it was. So they were brave enough and optimistic enough and believed enough that they put their children on these boats and sent them out to sea. And it took 10 years for the families to be reunited again. My parents were teenagers at that time and it somehow worked out. We were taken into this country as refugees. My parents went to high school and then they had me.

And then, I was surrounded by a support network that I found… I didn’t know it was as special as it was. I had teachers that cheered me on, rooted for me, and made sure that I had what I needed to succeed. And I ended up at Harvard and I’ve had the opportunity to become a physician. And even before CZI, even before Mark, I would be doing this work regardless because I knew it wasn’t fair. I knew that there were lots of kids just like me, who didn’t get the care, didn’t get the support that I had gotten.

And I know that our country, I know that our society is capable of this. And so, how could I give back? And so, I was an after-school teacher. I was a pediatrician. I am a pediatrician, and I tried to make that difference for the lives of other kids. I actually don’t know if I’ve been successful, but I do know that it’s hard for practitioners to do this work and that the systems aren’t designed for them to be successful. So that’s what we aim to do at CZI, make it easier for people to lift up others and do amazing work.

Sarah Neville: So you said the systems aren’t designed to be successful at this approach. Can you expand on that a bit? Where are the roadblocks, the obstacles that you’re trying to overcome?

Priscilla Chan: When I was a working in the classroom and in the clinic, you were siloed. You had sort of your lane that you were driving in. You were a pediatrician, drive in that lane. You’re a teacher, work in that lane. And you did your best, but you often were blind to what others were capable of being able to do together. And you didn’t have the tools or modern tools to be successful. Like we have in a lot of our personal lives, modern, digital well-functioning tools.

And so for us at CZI, we think about if we want to build a future for everyone, how do we actually empower teachers, scientists, advocates, to actually be able to collaborate with folks across silos, break down the silos. For our science work. We have bench scientists. We have computational biologists. We have user design experts. We have software engineers. We had advocacy folks, patient advocates, all working together. There’s no arbitrary silo and they can work together to find the best practice. And then the other thing that we do at CZI is we build technology. We listen to what the frontline practitioners want, and we see what is useful and can have impact. And we have a team of engineers that builds that in a durable, scalable way, so lots of people can have access to those great tools.

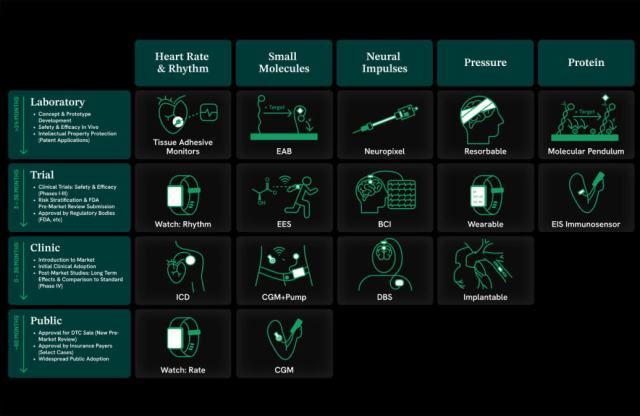

Sarah Neville: That’s fascinating. And I know you have this very bold ambition to cure, prevent, or manage all disease by the end of the century. I mean, can you explain… You’ve talked about this marriage between science and technology, but beyond that, is there a sort of particular approach or attitude that will set you apart and make CZI more likely to succeed than all the many researchers over 30, 40, 50 years who’ve been trying to cure cancer, for example. Something about your approach, a sort of kernel of it that you feel can be transformative here?

Priscilla Chan: So, first of all, I want to make it very clear. It is not CZI alone being able to cure, prevent, and manage all disease. We are in fact, working together as a giant ecosystem. And the example I’d like to give is that the NIH spends $30 billion a year on research in our country. We spend a tiny percentage of that, but it is our collective responsibility to actually work together. We are building off of the shoulders of those who’ve done that research ahead of us. And what we need to do is actually understand. First of all, be bold and optimistic. We intentionally set that audacious goal. One, because we know it’s possible.

If you think back, penicillin, not that old of a drug. If you think about SARS-1, it took us a year to understand the disease. And that was only 10 years ago. With COVID-19, we were able to characterize the disease within weeks. Progress is happening. And two, we have to think about how do we all work together? How do we link arms to actually make this not a zero sum game, actually something that makes it so that we can all work together and make each other better, which is why we’re so focused on what differential impact do we have to actually contribute to the ecosystem in a different way? Can we take on risk in our grant making in a different way?

How do we harness the power of patient advocates in our [inaudible 00:07:25] portfolio? How do we build tools that makes it so that not every single postdoc in the country doesn’t have to redo the first six months of their research process or analyzing their datasets? How do we make it easy to get to the innovation part, the collaboration part that makes science so fantastic?

Sarah Neville: So some of this is about sort of open source and making sure that anything you discover is made available to the wider research community, is it? Because I suppose commercial researchers necessarily have to sometimes sort of guard their discoveries, but is some of this about building that sort of open, transparent system where you do share what you find?

Priscilla Chan: Well, I think openness has a couple of things that are key to our principles in how we do science at CZI. One is the pre-print movement where we don’t encourage, and in fact, we encourage our scientists to do the opposite of hoarding data. Like if you’ve discovered something, the general scientific community wants to share it because they want to put it out into the world. They want it interrogated. They want others to know about it in case it can help others move along more quickly. That’s what happened naturally during the early days of the COVID-19 epidemic, people shared right away and made it so that every single other downstream research project could move just that much faster.

That is incredibly important. And so, we strongly encourage our scientists to participate in the pre-print movement. And we fund a group called Bio Archive to help make that possible in terms of a shared platform. We also believe in open source technology. We contribute to the open source movement, in part because there is a beautiful, robust, open source community in the scientific world. There are lots of tinkerers. They want to build great tools, and we are excited to be able to contribute to these tool sets that they’re building and sort of supercharge some of the more important ones.

But the other thing that is important to acknowledge is scientists don’t want to use tools that have been put into a black box and spits out an answer. That’s not satisfying to a group of people who want to understand. Literally, they’re trying to understand how the human body works. They’re not going to be willing to just submit themselves to a piece of software that doesn’t let them understand what even just happened with their information.

So we are deeply committed to that because that’s what the community wants as well. And the last part that I’m going to name that is super important to our sense of who else should be included in that research world is actually the patients. We have a portfolio of grantees that are actually just supporting patient groups that want to be engaged in the research projects, want to support the progress. And they bring their experiences and their medical information to help supercharge this research in part so that they can give back and they can be beneficiaries of the research.

Sarah Neville: And can you think of an example of where a patient advocacy group has really changed your direction or led to you focusing on something on which you wouldn’t otherwise have focused your scientists?

Priscilla Chan: Yeah, it’s not so much about us. We kind of see ourselves sometimes as the matchmaker here, but there’s examples of patient groups coming together to actually say… I’ll give you one example. I was at a Neuro Degeneration Network meeting, and there are lots of researchers studying Parkinson’s disease. And there was a few patients talking about their experience.

And in Parkinson’s we think a lot about the tremors. That’s a key symptom of Parkinson’s disease, but the patient said, “Hey, the tremor bothers me, but you know what really also bothers me is the fatigue. I’m just so tired.” How do we actually fix that? Or there’s this amazing advocate named Brian Wallach who was diagnosed with ALS a few years ago, and ALS is a super rare, somewhat orphan disease.

And if I were to ask, most people they’d remember that ice bucket challenge, but like is it actually a very super specific, rare disease? Or is it actually part of a broader disease cohort of neuro degeneration? And how can all these groups, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS come together to actually make progress, to unify patient advocates. And so what they’re doing is actually working on fixing a lot of these broken systems and silos. And I have to tell you, there’s nothing more motivating than hearing from a patient what their hopes and dreams are when they themselves are incredibly sick.

Sarah Neville: What truly matters to them may not be what the clinical community thought mattered, perhaps.

Priscilla Chan: That’s right.

Sarah Neville: That was fascinating. And I mean, you mentioned your focus on neurodegenerative diseases. And I was going to ask you, if one took sort of Alzheimer’s as a kind of worked example, very dreaded disease for which there’s currently no widely effective treatment, what can CZI achieve that hasn’t yet been achieved? But you just mentioned to me about looking beyond silos. So perhaps I shouldn’t just be asking you about Alzheimer’s, but about the whole family of diseases. But I’d be very interested to hear your thoughts on new approaches that you think can be effective there.

Priscilla Chan: I don’t have the answer, what is the new approach? But I believe in the same vision of breaking down silos. Alzheimer’s is actually a great example of where I think we just need to think differently. For a long time, we’ve been chasing these amyloid plaques that are present in the brain of Alzheimer’s patients. And we don’t really know why they’re there. No one has been able to say it causes Alzheimer’s disease, or it’s just related, or it’s a sort of random side effect that’s not related to the disease process.

It’s consistently there. So we’ve been studying it. And it’s one of the leads. But if you look at the broader scientific community, we’ve been focused on this one way, these amyloid plaques to understand Alzheimer’s disease. What we did instead was actually assembled the Neuro degeneration Challenge Network, where we said, “We want smart people who are interested in making progress in neuro degeneration, but you don’t have to be from the established cohort of scientists.”

You could be someone who studies the gut. You could be an immunologist. You could be someone who designs novel therapeutics. Come with your unique perspective. And that will help us better understand neuro degeneration more holistically because the immune system touches the brain. Your microbiome, which is so popular. And so hip to talk about impacts your brain health. And there’s, in fact, a whole separate nervous system that’s in your gut. And some people think that that nervous system is related to the one in our head. And so, we bring new people together. We say, bring your crazy idea. What are some new strategies that we haven’t thought of to break down the silos across even the way that we study the human body. And that’s what makes our work unique. Our vision is that we need to reconceptualize how we can make progress on neuro degeneration as a whole class, looking at different mechanisms, looking at different strategies to make sure that we’re really looking at all possible ways to make progress together.

Sarah Neville: That’s amazing. And I think you feel as an initiative, that imaging is very important, don’t you, to making progress?

Priscilla Chan: I’m incredibly passionate about our imaging portfolio. And in part for two reasons. One is if you can see differently, you can think differently and you can learn new things. And we’ve seen this time and time again in science. The discovery of the microscope, the ability to sequence DNA. When we saw and understand at different levels, we can actually do something differently. And then you’ll see whole new understandings of biology and then the therapeutics will follow.

And our imaging portfolio aims to say, can we see differently? Can we see at a sort of a protein level in a live organism? Can we connect different levels of granularity so that we understand and can see real-time what’s happening? And the other part that makes me excited is I feel that we can contribute to this space with our ability to be bold funders, to bring people from different sectors together, and to help build some of the open source software that this field needs rely on because these microscopes and imaging tools throw a ton of data.

And so, how do we make sense of it? And so I’m both passionate about it because we can see the world differently with these advances, and I think that with our skillset, we can do something meaningful to accelerate the field.

Sarah Neville: Science hasn’t historically been particularly diverse or inclusive. Has it? How do you ensure that the solutions you’re building are inclusive and representative of all the communities that you serve?

Priscilla Chan: I want to point out that there are many levers to make this change, and it is not a nice to have. It is actually key for us to be able to achieve our mission of curing, preventing, and managing disease for all. And right now, science is simply our science, the output of our science is simply not representative of all communities. Most research participants, most cell lines represent a middle aged man of European descent. You and I are not included in this data in a meaningful way. And when I go to the doctor, when you go to the doctor, we’re compared against those norms, that don’t necessarily tell us if we’re healthy or sick, or what is the best treatment for us. And that’s not all right. And so we’re doing a bunch of work to really understand, to contribute to diversifying the datasets that science is based on, looking at both ancestry and age.

We’re also supporting young scientists coming from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds, because simply different experiences and different backgrounds lead us to ask different questions and have different levels of sensitivity to what might be important to a patient. Multiple sclerosis is present in all genders and ethnicities, but multiple sclerosis in a white woman may mean different things than multiple sclerosis in a older African-American man. And that’s important. Being able to see those differences and be aware of those differences means that we ask questions and we conduct science differently. And so, we support ensuring that our future generations of scientists and physicians are of different backgrounds.

And also, we need to be doing this work internally. We have lots of experts that we work with, including Dr. Valentine, Dr. Hannah Valentine, coming from the NIH to help us make sure that we are asking those questions. And we are supporting a diverse perspective within CZI. We are majority women, about a third of our organization is from underrepresented backgrounds. And we come from a broad array of professional experiences. And so, we have the diversity of backgrounds and experiences to actually solve some complex problems. So we need to harness that together to make a difference. And that has to be resourced. We made a $500 million commitment to actually promoting racial equity, diversity, and inclusion in the work that we do, because we are trying to serve everyone.

Sarah Neville: And I know that another of your big focuses is the public understanding of science. That’s an area which has obviously probably never been more important than it has been during the pandemic, given the very high levels of vaccine hesitancy, particularly in the US. Could you tell me a bit more about that work and whether COVID has really kind of sharpened your sense of how important it is?

Priscilla Chan: Well, COVID has been a real accelerator of our work. We set our mission to cure and prevent and manage all disease. And we were building these future looking tools to be able to… We didn’t think that we’d be in a global pandemic at the beginning of 2020, but here we are, and we’ve been able to apply what we’ve learned in building tools and working with patient communities and the broader community in a very real-time way in COVID-19. One example that I’d love to share is we built a tool called Chan Zuckerberg ID (formerly IDseq) that it’s an open source software tool that allows scientists worldwide to sequence a sample and take that metogenomic sequencing data and identify a pathogen without having to need a prior hypothesis as to what was going on.

And we thought this would be… We used it. We saw it being used in Bangladesh, where they identified a new source of meningitis in children, but this was… We were using it in these interesting little pockets, but when COVID hit, we realized that we could shift that tool and build something called Chan Zuckerberg GEN EPI (formerly Aspen) to use locally, to allow departments of public health, to be able to sequence COVID-19 and understand the changes in variants in their community. But to make that really useful, we had to listen to public health experts on what they needed and how wanted the tool to be used.

So all of this came really real time, but then when it came to our ability to actually help serve communities through these vaccine efforts, which have been so inspiring, and also a lot of work, is that we have to listen. We couldn’t just drop off Chan Zuckerberg GEN EPI to the departments of public health and expect them to just pick it up because they have reasons why the way they’re currently doing it works better for them. They may have different needs, different concerns, different constituents in their community.

The same goes for people. I feel very strongly about vaccination, but someone else may not. And if I come in with their preacher mode, I’m going to miss the questions that are important to them. And there are a multitude of reasons why someone may be extra curious and have extra questions about the vaccine. We have historical racial issues in our country that make trust difficult. We have individual experiences that we need to take into account. And so we need to listen and we need to be able to actually meet those needs. And one way that we’ve done this, that’s been really inspiring to see our partners work is we realized that over the course of the pandemic, the Latinx population in San Francisco was disproportionately hit hard by COVID-19.

And so, we partnered with a local nonprofit to be able to administer tests and vaccines in the community and made it easy for them to actually get the help they need and the services that they need. And so, I guess my takeaway from all of this is like you can do great work. You can build great tools. But unless you truly listen, you’re not going to be able to have the impact that you want.

Sarah Neville: I liked the idea of recasting vaccine hesitancy as vaccine curiosity. That’s a nice formulation. Priscilla, I’m so sorry. The clock has beaten us. I could have taught for so much longer. I’ve very much enjoyed the conversation and thank you for making the time to be here with us.

Priscilla Chan: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Learn more about our work in science technology.

###

About the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative was founded in 2015 to help solve some of society’s toughest challenges — from eradicating disease and improving education, to addressing the needs of our local communities. Our mission is to build a more inclusive, just, and healthy future for everyone. For more information, please visit chanzuckerberg.com.