May 9, 2023 · 9 min read

Gustavo B. Menezes’ Mission To Increase Access to Bioimaging Equipment With Labs Around the World

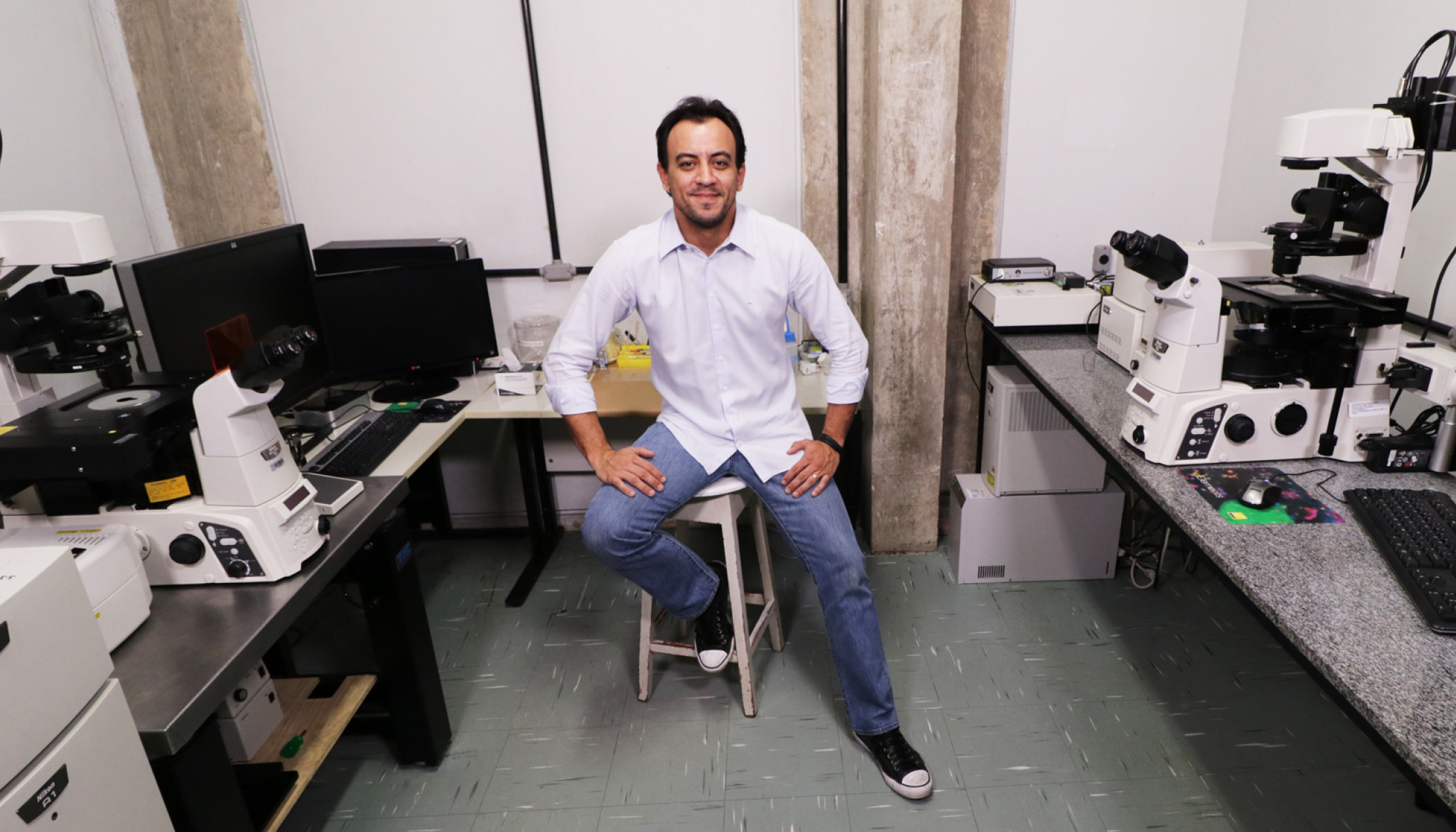

Biologist Gustavo B. Menezes first encountered in vivo imaging while defending his doctorate thesis and thought, “why have I not used a bioimaging microscope earlier?”

Imagine playing chess without knowing all the rules. The analogy, adapted from renowned physicist Richard Feynman’s explanation of attempting to understand natural phenomena, was more or less what biologist Gustavo B. Menezes, of Brazil, experienced before he was exposed to a new world in imaging.

“I remember it just like yesterday,” Menezes says of the moment he was introduced to bioimaging. “It was love at first sight.”

The most routine lab microscopes work well to examine isolated samples of tissue extracted from a living subject. Those were the ones available to Menezes and his colleagues in Brazil at the time.

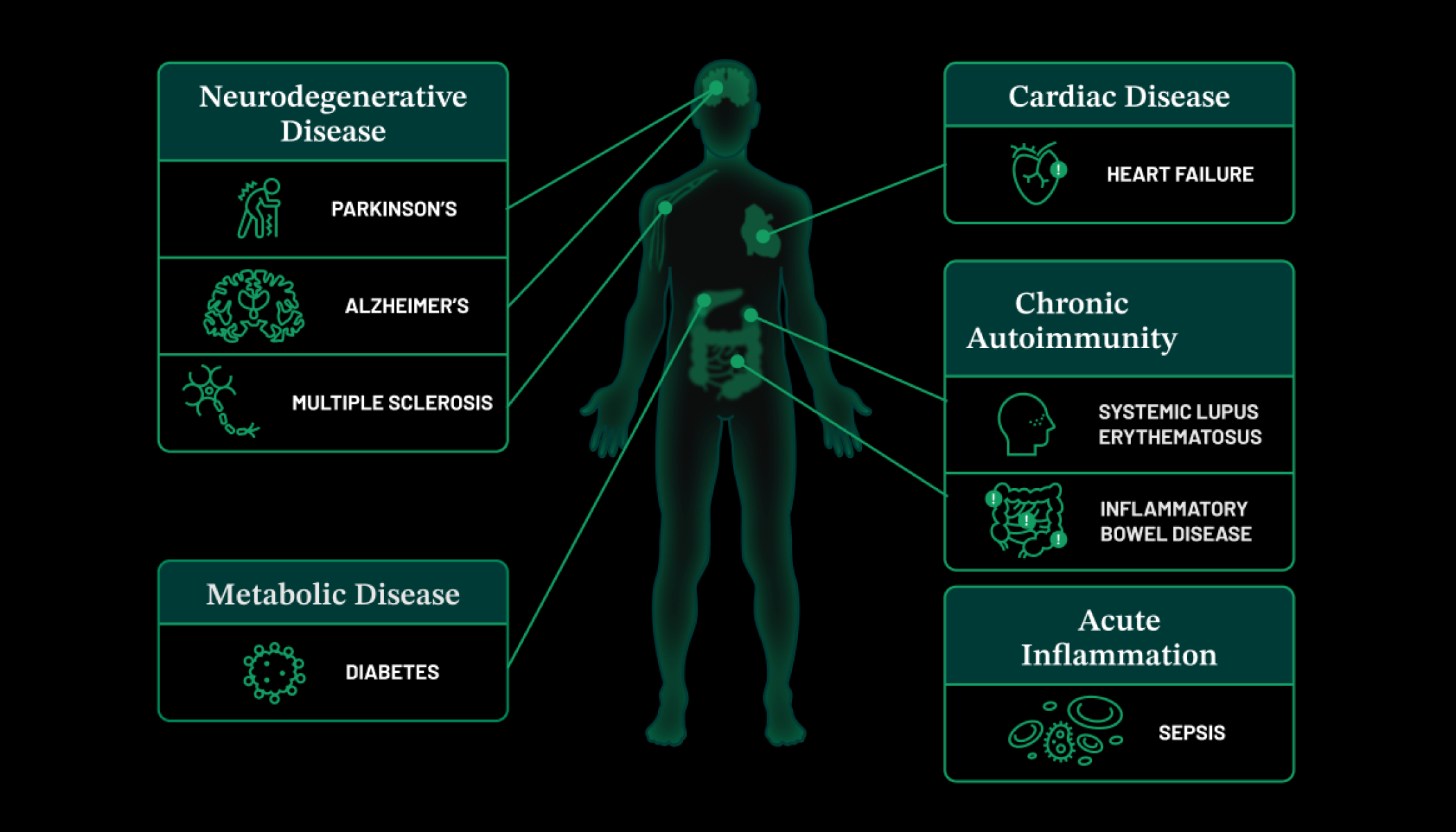

More advanced microscopes, in contrast, allow researchers to examine biological processes within a living specimen — or, in vivo — in real time and all at once. Whole organs or even an entire living specimen can be imaged while it conducts its normal biological functions, giving researchers the ability to witness interactions at various levels of cell structures.

“[Knowing] how cells connect, how cells kill bacteria, how a molecule travels from one place to another,” Menezes explains of its application, “this has opened huge doors in our knowledge about biology.”

Access to what Menezes called “a whole new world” in biology, however, was limited in Brazil due to the prohibitively high cost of bioimaging microscopes — but he was determined to change that.

Thanks to a chance encounter with a technician who taught him everything he needed to know about the equipment’s specifications, Menezes spent the next several years redesigning bioimaging equipment, ultimately bringing the cost of a microscope capable of in vivo imaging down to a fraction of what it was.

Menezes then shared the redesign with the rest of his country with the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s support, emphasizing access to more remote labs and scientists of all skill levels.

Today, Menezes and his team are able to visit labs in all 26 states of Brazil to advise and support other researchers in building or acquiring their own bioimaging microscopes based on his redesign, which has since led to the publications of more than 120 research papers by scientists who otherwise would not have access to the tools necessary to conduct their research.

Early Years in Bioimaging

Menezes has spent his life dedicated to the sciences, completing a master’s degree in biological sciences and doctorate degree in physiology and pharmacology. But it wasn’t until the end of his doctorate that he first encountered bioimaging. He was presenting his thesis defense when a professor in the committee suggested he use in vivo imaging in his research.

“What? How can I do that?” he recalls thinking at the time. “It was completely new for me, anything about microscopy and bioimaging.”

Funding for labs in Brazil is hard to come by, Menezes says, and at the time, equipment that allowed researchers to examine whole, live specimens in real time was either limited or not accessible by students.

The following day, Menezes met the professor in her lab, and she showed him in vivo images of a live mouse’s muscle.

“I could see with my eyes in a microscope how beautiful vessels can work in vivo, how the blood flows inside vessels,” Menezes says. “All those features in books, all those immunological concepts that I used to learn in the classroom, they were just in front of my eyes in that moment.”

During his post-doctorate in pathology and cell biology, Menezes pursued an opportunity to study at the University of Calgary in Canada, where he expanded his work with leaders in the bioimaging field and state-of-the-art equipment.

Also read: A Day in the Life of an Imaging Scientist: Laura Waller

But Menezes was torn as his training came to an end. He knew that many Brazilian researchers continued their careers abroad, where they would have access to grants, labs and budgets that weren’t always available in his home country. Menezes was worried the science field in Brazil was still in its infancy and believed that funding his research would be all the more difficult due to budgetary restrictions and bureaucratic challenges.

“What are you doing to solve the problems you are complaining of?” he asked himself before ultimately deciding to return to Brazil with a new drive to make a difference.

A More Cost-Effective Way To Bioimage

The biggest obstacle to increasing accessibility to bioimaging equipment is the cost, with a single in vivo microscope easily costing over $1 million USD — a price restrictively high in Brazil and similar countries.

But another equally as significant challenge, Menezes explains, is paying for maintenance and repairs, which grants often do not cover.

“Eventually, you buy equipment and then it has a minor issue,” Menezes says. “Since you don’t have money to fix it, it stays broken. It’s even easier to apply for new equipment than to apply for money to fix broken [equipment].”

Researchers, therefore, are hesitant to use the equipment for fear of breaking it, and the equipment is often reserved for experienced researchers, meaning students frequently don’t receive training to use bioimaging microscopes.

Menezes’ solution to these challenges came to him during his work in Canada, when his lab ordered new bioimaging microscopes. During the equipment’s delivery, Menezes approached the specialist and asked if he could help with the installation process. He explained to the technician that he wouldn’t have the budget to pay for assembly and repairs once he figured out a way to fund a microscope upon his return to Brazil. He wanted to learn to do it himself.

“He always thought that I was crazy as a postdoc who wanted to help a technician assemble a microscope,” Menezes jokes.

What he learned in that time, though, was invaluable. At least half the components that go into the bioimaging microscope as it is designed was not essential to Menezes’ intended use and he knew that he could bring down the cost significantly if there was a way to opt out of certain features.

When Menezes eventually returned to Brazil after completing his postdoc, he reached out to the microscope supplier, and discussed adjustments and omissions from the final product without compromising the quality of research it would produce, ultimately bringing down the price of the microscope to about a quarter of its original cost.

“The first images, they were so, so beautiful, and so much better than the images that used to be done,” Menezes says.

When a colleague heard of Menezes’ more cost-effective design, she asked if he would be willing to help her. The lab where she worked, located in the northern Brazil state of Rondônia that borders the Amazon, had acquired funding to purchase a bioimaging microscope, but she needed guidance in purchasing the relevant parts and instruction on its use.

Though the lab is located more than 1,800 miles (3,000 km) away, Menezes jumped at the opportunity and once a month, he made the cross-country journey from his own lab to work with her and her students.

Over the next several years, Menezes worked with her team of scientists — showing emerging indigenous researchers and students from working class neighborhoods ways in vivo imaging can bolster their research and training them to use the microscope he designed.

“They just explode my mind with great ideas … it’s so emotional for me,” he says, adding that by expanding access to jobs in science, “we’ll change Brazil’s history forever.”

As for the first microscope that Menezes modified 15 years ago, he says it continues to be a staple in his lab.

“It is still running today,” Menezes says, “and helping me not only to publish covers of high-profile journals in the world, but also educating a generation of scientists that are now also capable … in bioimaging.”

Bringing Bioimaging to the Rest of Brazil

Armed with the technical skills to assemble a lower-cost microscope that is just as efficient, Menezes wanted to continue sharing in vivo microscopy with the rest of Brazil — namely, labs that typically receive significantly less funding than the Federal University of Minas Gerais, where Menezes is based.

The solution Menezes was seeking arrived in the form of a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

CZ Science Imaging Program Lead Vlad Ghukasyan explains that they got to know Menezes’ work while they were seeking grant candidates in countries underrepresented in the global science community for the Expanding Global Access to Bioimaging RFA. The goal of the program is to not only drive the development and dissemination of new scientific technologies in the imaging realm, but to ensure equity in access with a focus on representation and diversity.

“Diversity moves science forward,” Ghukasayan says, explaining that the research developed by scientists of different backgrounds and perspectives has been imperative to recent breakthroughs and expansions of various fields. “We wanted to ensure that everyone everywhere would have equal access to the technology to advance their science — whatever their local science would require and whatever global science would require.”

Also read: 3 Scientists on Advancing Biomedical Science in Latin America

Menezes’ dedication to equitable access and commitment to elevating institutions that have less funding, alongside an impressive portfolio of research achievements, made him a clear fit for collaboration.

“He helps these underfunded labs upgrade their research microscopes with a relatively inexpensive module that would help take their science up a notch — a big notch,” Ghukasayan says. “What he also does [in turn], is inspire or persuade people to do sciences. He is very passionate about that.”

Like he did with his colleague’s lab and researchers in Rondônia, Menezes and his team leverage their CZI grant to work with labs across Brazil, helping order and build bioimaging equipment based on different needs and budgets, and advising in ways in vivo imaging can bolster their current body of work.

“We want to plant one seed in every single state of Brazil,” Menezes says, “ [and] we hope that we grow a beautiful garden of bioimaging scientists in a new generation.”

Learn more about CZI’s imaging program and its commitment to develop new imaging tools and robust frameworks to quantify, analyze and share imaging data and methods.