Oct 30, 2019 · 18 min read

Broadening the Definition of Student Success: A Spotlight on Mental Health

This week, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) Director of Whole Child Development Brooke Stafford-Brizard spoke to a crowd of more than 1,000 education and technology leaders at the annual iNACOL Symposium in Palm Springs. Brooke spoke about the need to take an asset-based approach to mental health that infuses teaching of mental health skills into schools with the same intention and rigor we give to academic skills. This important shift is part of CZI’s mission to ensure that every student —not just a lucky few—can get an education that’s tailored to their individual needs and supports every aspect of their development.

Here are Brooke’s remarks as prepared for delivery:

Thank you. I’m thrilled to be part of a conversation about the future of learning since this is core to our work at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Our vision is to equip all students with the knowledge, skills, habits and agency to thrive in a changing world. We focus on this broader definition of success because we know from research and from the wisdom and experience of educators that success in young adulthood requires far more than we capture in the high school diploma.

If we only name that limited set of academic competencies as preparation for postsecondary that is where the majority of resources and the majority of energy will go – we have to change our north star to reflect what we have learned to be critical for our children’s success academically and beyond.

We are committed to leveraging personalization to support efforts toward this broader definition of success – what I mean by that is understanding the unique strengths, passions, context and needs of every student and tailoring the learning experience and environment to that.

As we think of the areas of development involved in this broader definition of success, what pictures come to mind when you think of:

A student thriving academically?

A student thriving physically?

A student thriving in their mental health and wellness?

What came to mind here? Do you start or even land with what this student wasn’t? Stressed, anxious, depressed?

Many of us don’t have a concrete picture of what mental health looks like through an asset based, strength-based lens and without that, it is impossible to connect to the skills and conditions that we need to focus on to support the mental health of all of our students.

Without that clarity, we are faced with the reality that most schools are not set up to rigorously and intentionally address an area that we know is critical for our children’s success inside and outside the classroom – we know it is critical in the face of mounting evidence, mounting demand from families and educators and in the resources that we are starting to see directly allocated to the space in a number of states.

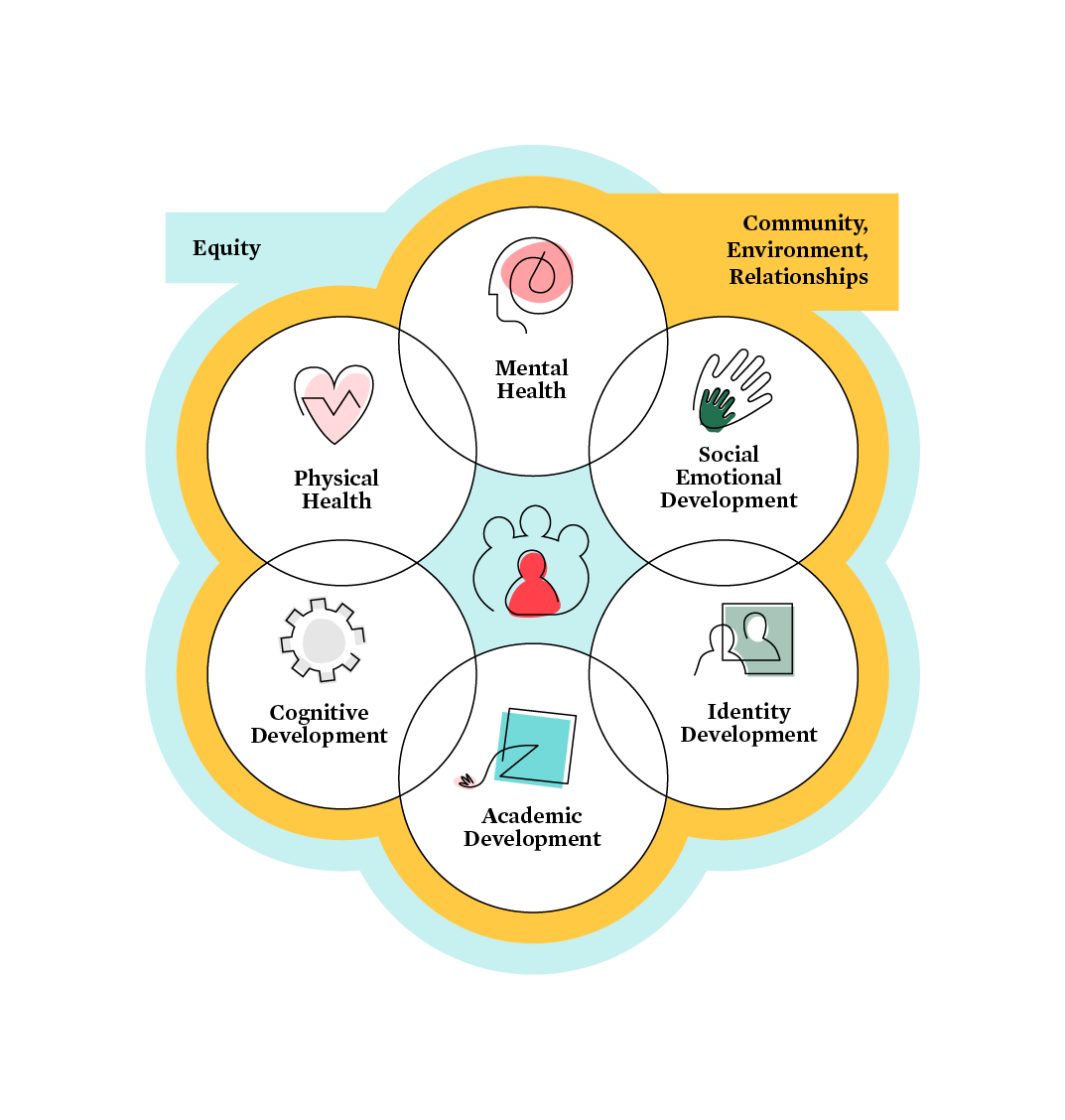

Mental health is an area that we name in our whole child approach to personalization at CZI.

This whole child approach is grounded in equity and focuses on the assets that students bring from their background and culture. We must ensure our learning environments are respectful and responsive to those cultures and experiences, and if we see gaps associated with race or income in any of these areas we address through focusing on the skills the student needs to develop but just as much on how environments and relationships around that student are structured to deny or limit their healthy development.

With this approach in mind, I want to focus in on mental health this afternoon – I want to share the incredible demonstration of need and demand for prioritizing this area and then focus on two specific goals: clarity around how to define mental health through an asset-based lens and the skills and conditions that contribute to mental health. In addition, I want to provide clarity on what concrete supports in classrooms and schools look like so we can move from the why to the how– and understand the shift that many of our schools want to and need to make.

What this shift looks like

To give you a sense of the shift I’m describing, I want to start by putting it in terms of what a school day today might look like for a student and a teacher — and then, what it could look like if we were serious about structuring our schools in ways that support both of them better.

Let’s consider the day in the life of a student in our current structure:

Christopher is 15 and a 9th grader at a larger high school in a mid-sized city. By the time he gets on the bus, his mind is swimming with thoughts and emotions and the coming school day is only part: His dad is battling cancer, he’s experiencing confusion and anxiety around relationships with friends in this new high school environment and deadlines and responsibilities piling up.

With no space to put all of these thoughts and emotions, he feels forced to try to suppress or ignore them as he heads into first period math class which he does without connecting with one peer or adult. There is one teacher he connects with – Mr Hillman, but they never have the time or space to meet and if they do set it up it is cancelled constantly.

Christopher makes it through his classes trying to stay under the teachers’ radars. He sees school as his job but not something that he feels connected to or passionate about. By the time he is on the bus home he is overwhelmed and exhausted with unresolved emotions about his dad and his friends and an evening of homework ahead of him.

Now let’s look more deeply at the experience of one of Christopher’s teachers, Mr. Hillman.

Kevin Hillman feels behind before his feet hit the ground in the morning. He and his wife race to get themselves and the two kids out of the house. The frenzy of the morning nevers seems allows him to check in with his kids the way he wants to – what are they excited about with the day ahead? Worried about?

His mind shifts between his own kids, the dozens of students that are on his mind, and his science lessons for the day. Those lessons are underway before he knows it and his experience toggles between the joy and purpose he feels when he is immersed in lessons and lab work with his students and the stress that mounts as the list of students who he is not reaching grows with each period of the day.

Some students explicitly act out, and some are just disconnected, Christopher is one of these students. For a number of them like Christopher, Mr. Hillman knows there is a deeper issue of trauma or stress that is impacting them but he cannot seem to carve the time in his day to focus on connecting with those students.

He ends his day with a mixture of gratitude for his family, guilt for not being there enough for his own kids and a sense of stress that emerges from his deep empathy for his students that he knows need more than science instruction and a sense of inade and frustration that he is able to meet those needs.

But this doesn’t have to be Christopher or Mr. Hillman’s experience.

What if Christopher felt seen? Connected to himself and others? What if Kevin had the supports and dedicated time in place to prioritize that time with Christopher? And to process his own stress and prioritize his own wellbeing?

There probably isn’t an educator in this room from classroom teacher to system leader who doesn’t understand the importance of what I am laying out. But we lack the structures and systems to make what we value and long for intentional, accessible and actionable.

Let me bring that to life. I want to show you some clips from one of our partner schools that you might have heard about – Valor Collegiate in Nashville. What you’ll see here is an instructive practice. Let’s just watch what it looks for a child to be seen and valued and supported:

I’ve seen again and again the impact that this practice has on students’ personal growth and the growth of the community driven by trust and vulnerability And Valor’s teachers? They experience the same opportunity to build trust in a space of vulnerability and support.

This is a lot bigger than any one practice or structure — the circles are just an example — it’s a willingness to rethink the school’s structure, schedule, staffing and more to serve kids’ emotional and mental-health needs as well as academic ones.

I don’t need to convince the educators and parents here or the students that you serve that this is a priority – we have already heard it straight from you. Parents name mental health as the most important skills for their child’s success, and reading is second. Teachers name it in the top five.

In a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. teens ages 13 to 17, 96% named depression and anxiety as a problem among their peers, 70% of them naming it as a major problem.

Marc Brackett and his team at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence have interviewed thousands of students and teachers and their predominant emotions are not great.

I know I took us right back to a deficit frame here, but we cannot turn away from the as a profound expression by our youth, our families and our educators that this matters and that there is desperate need for support here. When we turn to the supports to address this need, we turn back to an asset-based definition of mental health so let’s take a closer look at that.

What do we mean when we say mental health?

Mental health is a broad term — far more so than in typical usage. It’s much more than freedom from pathology. What we are talking about is not just the absence of the negative that allows our kids to function; this is about what makes students engaged, whole people who thrive–who are connected to ourselves, to others and the world – so we aren’t just talking about a set of internal skills here.

A couple of frameworks are helpful in understanding what that looks like from an asset-based lens.

The framework from the Center for Healthy Minds centers on four important areas:

- Awareness – presence and focus on present experience

- Connection with others – empathy, compassion, gratitude

- Insight – self awareness including understand we change and evolve as we grow

- Purpose – intention to accomplish something that is meaningful to oneself and of consequence to the world beyond one’s self

Each one of these areas is complex and hardly something we can snap our fingers to achieve for our students – we progress toward these outcomes associated with wellbeing by developing skills and conditions that drive them.

If we think of mental health through an asset based lens – not as depression, anxiety, suicidality – we place a primary focus on the skills within a framework like the Building Blocks for Learning.

This is a framework I developed in partnership with Turnaround for Children, drawing from the fields of developmental psychology, cognitive neuroscience and social psychology to propose a developmental path for non-academic skills and mindsets. Drawing from the cornerstone of development as healthy adult attachment, the framework proposes the skills and mindsets that contribute to higher order skills like resilience and self-direction.

Upon engaging multiple mental health experts in the field, we have confirmed the overlap with this framework and the foundational set of skills connected to wellbeing. And in it we see skills commonly connected to SEL, within the research on mindset, and with the focus of a trauma informed environment.

If we narrow in on resilience –that ability to weather challenge and adversity and to recover from setbacks is an imperative focus for students in the midst to trauma and adversity and something that every individual needs to develop–research demonstrates that the skills under resilience in this framework are key contributors to its development BUT resilience also relies on supports outside of the student like relationships, community and connection to culture.

That goes for all of the skills and mindsets here – their development relies on both rigorous instruction grounded in the science of learning and on intentional design within the environment and relationships around students.

Why does mental health matter?

We could spend the rest of this hour and the rest of this conference demonstrating the connection in the science between mental health as we are defining and learning. We have partnered with multiple organizations to codify and continue to build this evidence and it is there from birth through adulthood from the fact that connection and relationships with others actually build our brains beginning in infancy to a sense of purpose acting as a core driver of perseverance in college.

Our emotional state and social connection serve as the gateway to learning. As humans our evolutionary success is due to successful response to our emotions and roles within a social structure.

Because of this, these functions of emotion and social belonging and connection are intertwined with our cognitive processes; they drive our attention, memory, decision making and motivation. Within the immediate process of learning, these functions are precious and limited. Which means we cannot afford to not to focus on our students’ mental health when it comes to learning.

The implications here are particularly profound when it comes to equity or ensuring that race and income do not predict any of our students’ outcomes. We know the impact that chronic stress often correlated to poverty has on the centers of the brain responsible for cognitive processes like attention and memory.

But how are inequitable environments impacting students’ mental health? How are we denying belonging and connection when we fail to recognize students cultures and ensure that they see that reflected in our schools? How are we impacting their awareness and insight when we fail to address implicit and explicit bias within our schools? For many of our students imagine how these experiences must impact those precious and limited cognitive function.

It is critical that we continue to invest in the science to answer these questions, but we often anchor so much in the evidence for why this matters that we fail to get to concrete implications for practice so I want to get there.

But before I transition, I want to share one compelling study – researchers put 4-year-olds on a swing set and either swung them in synch or out of sync. Then they brought them back into the classroom to complete a task. The children who were swung in unison were better listeners with each other, more effective collaborators and more effective at completing a task together.

That connection to others and what it means to be in sync feels like something intangible but we have empirical proof that it matters deeply. I share this not to suggest everyone walks out of here to build the synchronous swinging program.

The message here is intentionality. We don’t leave learning algebra or persuasive writing to chance hoping our students just develop those skills – we design, plan and teach with rigor and intention and building an environment that supports mental health and wellbeing requires the same commitment. You can just cross your fingers that the students connect by swinging in sync by chance.

What does it look like to support mental health in schools effectively?

The next few days will provide the opportunity to get much more granular with guidance for how to implement with intentionality, personalization and rigor. The Turnaround for Children team will be presenting a few times, including Pam Cantor focused on drawing from the science of learning to support whole child development and a deeper dive into the Building Blocks for Learning on Wednesday. Tomorrow morning, DC Public Schools is doing a session on using brain science to personalize learning. And tomorrow afternoon, there’s a session on belonging and it’s importance to healthy youth development.

We bring this work to life in practice in three areas all of which are critical to success: skill development, relationships and environment.

Taking this on is far more ambitious than a program or intervention. It’s a fundamental shift in how we see the purpose of school, and that fundamentally changes structures, schedules, staffing–not just at the school level but the district/org/leadership level too. We need a design lens to this work not an intervention one.

How are we at CZI helping?

We are taking learnings like the examples I shared with you today and are using them to drive our investments and partnerships in the field. We are leveraging the phenomenal work that our partners have done synthesizing the science of human learning and development to inform our investments bringing this to practice.

We believe this work requires a rethinking of partnership, setting a different table to foster collaboration across the domains of our framework. We want to bring researchers and practitioners together and when we say researchers we mean educational researchers as well as public health researchers, social psychologists and neuroscientists–and when we say practitioners we mean educators as well as pediatricians, social workers and community organizers.

And we want these partnerships to be collaborative from the start – we believe the work of researchers will be most applicable and most impactful if they design in partnership with practitioners from the start and our educators were not trained through a lens focused on human learning and development so partnership with expertise across domains in this framework is critical for innovations in whole child practice.

We can’t address huge issues in the space of mental health like significant trauma in our schools without partners in clinical psychology and social work, or support building stronger belonging with students of color without engaging partners like social psychologists who study racial and ethnic identity development.

How can you get started?

I’m incredibly excited and optimistic about what schools can do for kids — everywhere, in every type of community — when they begin to see mental health as a core priority. This can’t be about quick, dirty and cheap. Don’t just go to Valor, start a circle at your school, and check this off the list. It’s a fundamental shift, not just an intervention or added class. And we have seen partners do this.

Different leaders have taken different approaches, like our colleagues at Valor Collegiate academies, who use the Compass model with students and adults, and our colleagues at Van Ness Elementary school in Washington DC, which has incorporated a deep study of the science of human development with book clubs, a partnership with transcend and a focus on conscious discipline.

Whether you are designing a school, improving an existing school or transforming a system, you need conviction, collaboration and creativity.

Conviction – This starts with a mindset shift that has to permeate your school or district/charter management organization. Perhaps you are there but is there conviction that this matters from the classroom to the board?

Across all of our partners who have successfully integrated whole child practice, there isn’t one who didn’t start with their adults – and that includes a shared commitment to truly prioritizing this, capacity building through key partnerships and attending the mental health and wellbeing of the adults themselves.

Collaboration – What does your reinvented partnership look like? If you lead a school, a school system, or you support schools in some way, and are ready to head down this road, set a different table of authentic partnership — if you’re a district team, this is your priority. You have to go back and think beyond one-off partnership with these areas of expertise — these areas of expertise have active seats at the table.

Creativity – Clearly, this important work cannot be done without resources behind it and that requires creative pursuit of additional resources and creative use of current resources. We are seeing funds routed toward mental health through grants programs at the Federal level and increasingly at the state level. And partners like Van Ness in DC and other schools we have learned from use their social workers, school psychologists and even nurses in intentional and strategic ways not just to intervene with a small set of students, but to impact the way relationships are support and instruction is designed and delivered across the community.

In the end, over 20 years in this work leaves me humble about the scale of the challenge, how far we have to go before we can say we’re meeting most of the needs of the majority of our kids— and yet, optimistic, because the hunger for education to be more grounded in a holistic approach is so great among students, parents and teachers.

Thank you for what you do and we look forward to continuing to partner with you to do this important work that reinforces why so many of us came into the field of education: to connect to and support the healthy development and success of children.