Voices of Change

Meet change-makers across CZI’s work in science, education and California’s Bay Area community as they reflect on their learnings and impact.

We’re on a mission to help solve some of society’s toughest challenges — from eradicating disease and improving education to addressing the needs of our local communities.

This mission isn’t a solo endeavor. It’s a collective effort advanced in partnership with organizations around the world.

Voices of Change introduces you to some of these partners — including school leaders, scientists and community organizers.

Read their stories to learn more about what it’s like to accelerate progress toward goals, what motivates them when they encounter challenges, and why they’re dedicated to building a better future for everyone.

These interviews have been edited for brevity.

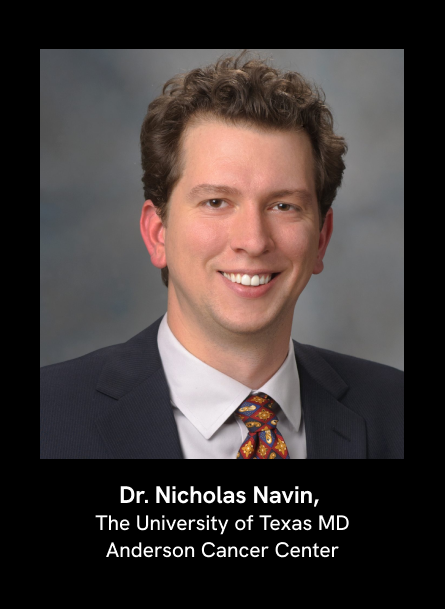

Dr. Nicholas Navin: Creating the Human Breast Cell Atlas

Dr. Nicholas Navin is a computational biology expert and a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. While completing his graduate and postdoctoral training at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, he published one of the first methods for analyzing DNA from a single cell. More recently, Dr. Navin and collaborators Dr. Kai Kessenbrock, Dr. Devon Lawson, Dr. Bora Lim, and Dr. Alastair Thompson created the world’s most comprehensive map of normal breast tissue, the Human Breast Cell Atlas. This atlas provides an unprecedented roadmap that may help identify treatments for breast cancer and other diseases.

1. What is a pivotal learning or “aha moment” in your career?

While a postdoctoral fellow at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, I studied cancer genetics and tumor differences. I found it frustrating that we couldn’t figure out how many different cells were present in a tumor. At the time, genomic techniques were not sensitive enough to study individual cells, so cells were profiled in bulk. Bulk genomic methods such as microarrays didn’t provide the answers I was looking for. During my thesis, I did a lot of work to figure out how to capture single cells, amplify their DNA, and then profile them using genomic technologies.

The genomic profiling using microarrays never worked well. I shelved the project for a while, but I thought I would try it again when Cold Spring Harbor got access to some of the first next-generation sequencers — like super-readers of our genes. I remember getting my first data back from one of those early sequencers on single cells and was so excited to have the data I needed finally. I realized, “OK, well, this can really work.”

Many others worked on single-cell RNA sequencing at the time, including Stephen Quake (now head of science at CZI) and Fuchou Tang. Many of those early meetings were fun because we would talk and compare notes. Everybody knew it was hard to do, but everyone was excited about the type of data it could generate. Then, it became commercialized, and that’s when things took off. Now, single-cell sequencing has become a very common technology people use worldwide.

2. What is the big-picture question your research aims to answer?

One of my motivations is that we worked a lot in breast cancer research using single-cell methods to study many cell types in the microenvironment. Like many other projects, we realized we needed a Human Genome Project-like reference where we can say, “This is actually normal and not something that’s cancer or disease-specific.”

Around the same time, about seven years ago, I was at a meeting at Stanford University with two other co-leaders, Kai Kessenbrock and Devon Lawson, where early-phase cell atlases were being discussed.

At the conference, we realized no one else was working on a cellular map of the breast. So we immediately said, “Gosh, we really need to do this for normal breast issues.”

3. What are you most proud of about your work on the Human Breast Cell Atlas? Are there any measurable impacts you can share?

I’m proud that the Human Breast Cell Atlas reached this very mature point after many challenges and that the data is out there. I was excited to see so much interest when the paper came out. We’ve received positive feedback from different areas of the scientific community — people working in lactation and breast cancer.

We hope it’ll be widely used because we put so much time and effort into it and made it and all the protocols open access.

4. What advice would you offer to early-career scientists?

My advice for young scientists is to have three projects. The main project is crucial because it’ll help a young scientist get published and into the next stage of their career. Having a medium- and high-risk project running at the same time can lead to big discoveries. It’s also important to consider when to move on from them or take a break when they’re not working. It’s also okay that many projects will fail — go back to them and try again. That’s what the single-cell DNA sequencing project was for me.

5. What is your favorite activity outside of work and why?

I love spending time with my 7-year-old son outside of the lab. We do a lot of combat robotics together, where we build robots and fight each other in national competitions. I find that very stress relieving. Also, I always like to get some exercise in my day. I bike to work as much as I can, and that helps me clear my head.

Read more about Navin and his work on the Human Breast Cell Atlas.

Tony Monfiletto: Remodeling Education From the Community Up

Tony Monfiletto is the executive director of Future Focused Education, an organization on a mission to create healthier, prosperous communities by advancing the best education for the students who need it the most. He is passionate about finding innovative solutions to our most challenging public school issues and preparing young people for a dynamic future. CZI partners with Future Focused Education to support its work to more broadly define and measure student success, where community-driven graduate profiles and capstone projects for high school students are key components of the innovation happening across the state.

1. What are the specific challenges that your work addresses?

Our work specifically addresses the untapped assets of the young people in our state. We know our students are capable; they just need opportunities to prove themselves. Social and economic inequities have persisted for generations due to colonialism, and the past few years have been particularly difficult for adolescents in our state. Ultimately, our goal is to change the subtext of our system that tells them, “You can be successful because of who you are and where you come from rather than in spite of it.”

We do this by engaging young people in real-life problem-solving in their communities. When young people are given the opportunity to use their skills and talents to make a difference in their communities, they are more likely to stay engaged in school and set their sights on a bright future.

Through our partnership with the New Mexico Public Education Department, Future Focused Education implemented the Innovation Zone Initiative in 20 local education agencies. This initiative is designed to take advantage of the local wisdom in our state by connecting young people to local collaborators through work-based learning and community-based capstone projects.

This approach will help create a more equitable and just education system in New Mexico where all students can succeed.

2. What is a pivotal learning or “aha moment” in your career?

I began my career as a legislative staffer responsible for the state education budget, which fully funds school operations in New Mexico. (We do not use local taxes to support schools.) My responsibility was to build the appropriations strategy to ensure equity. After four years of developing the state public school finance strategy, I realized I was unprepared to do the job. I had no idea what actually happened in schools and couldn’t see the relationship between funding and the impact on young people and their communities. As a result, I left and became a teacher and school founder, ultimately leading me to a career building the landscape for change at Future Focused Education.

3. What are you most proud of about your work?

We are making a difference. For example, Future Focused Education has served over 1,500 students and 250 employers in our paid internship program. Based on an external evaluation, we have found dramatic increases in student skill levels and significant increases in social capital. The program is the template the state uses to scale work-based learning across New Mexico through the Innovation Zone initiative. This is particularly remarkable given the lack of large employers in our state.

4. What is your favorite activity outside of work and why?

I commute by bike every day to work, and I take long rides on the weekends. Albuquerque is my home, and it is a beautiful place to live. I see it with fresh eyes daily and recommit to my life’s purpose. It also keeps me mentally and physically fit.

5. What book would you recommend to someone who wants to understand your work better?

“Tattoos on the Heart” by Father Greg Boyle.

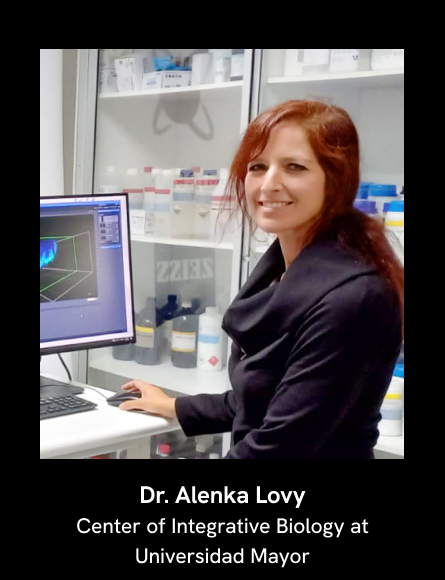

Dr. Alenka Lovy: Expanding Access to Advanced Imaging Technology

Dr. Alenka Lovy is an assistant professor at the Universidad Mayor’s Center for Integrative Biology in Santiago, Chile, and the principal investigator of the institute’s light-sheet imaging initiative, LiSIUM. As part of CZI’s Expanding Global Access to Bioimaging program, Lovy’s team seeks to comprehensively introduce light-sheet microscopy to a new generation of scientists in South America. Originally from the Czech Republic, Lovy earned her master’s in plant physiology from Washington State University and her doctorate in plant biology from the University of Massachusetts.

1. What’s the mission of your work?

I’m working to expand access to advanced imaging technologies to researchers in South America. When my department acquired a ZEISS light-sheet microscope, it was a huge achievement for Universidad Mayor and the researchers here focusing on developmental biology. Light-sheet imaging lets you image 3D organisms whole, live and quickly. Or, if you’re working with tissues like brain tissue, you can get excellent 3D volume imaging quickly. So people working with these brains could spend months on the confocal microscope, whereas with light-sheet, it’s done in a week or even a day.

It’s fascinating because I’ve been working with many microscopes, and the ZEISS Lightsheet is not something I’ve come across. Our biggest mission is to share this technology with others because it’s the only one of its kind, basically on the continent.

At first, we began to build networks of researchers and spread information that we have this instrument available for use. Now, we’re focused on building three more affordable light-sheet microscopes, which are portable, and donating them to Brazil, Uruguay and Chile. That way, the microscopes won’t have to cross borders — a difficult feat due to import fees and laws. Instead, researchers can travel with them within each country. It’s challenging to come by this costly technology in South America. So, the idea of traveling with this technology or sending it to people who need it is very exciting.

2. What are some examples of how light-sheet access has been helpful for scientists’ research?

Examples of light-sheet microscopes impacting discovery include research on Huntington’s disease and zebrafish eye development. Researchers were able to image live zebrafish over more extended periods and image their brain samples so much faster than on the confocal microscope.

3. What are some of the challenges you have faced in your work?

Even though we now have access to light-sheet microscopy, I’ve been surprised by the slow adoption rate of the technology by other researchers. Many researchers are apprehensive about using the microscope out of concerns that the technique may become too expensive in coming years. Despite these challenges, training students on it in our workshops has been incredible. We took a light-sheet to a developmental biology course, and students stayed up until 3 and 4 a.m. imaging.

4. What are you most proud of about your work?

I enjoy the collaborative nature of science in South America. The scientists collaborate amazingly. I hope these microscopes’ ability to travel across different institutions will help accelerate collaboration even further.

5. What is your favorite activity outside of work and why?

I love hiking with my family on the weekends. It’s been raining more than usual, and the mountains are beautiful and green. All the seeds have been waiting for water, and now they’re finally getting it.

Read more about Lovy and her work to increase access to advanced imaging tools in South America.

Mirna Cervantes: Increasing Opportunities for Immigrant Families

Mirna Cervantes is the executive director of The Multicultural Institute (MI). Founded in 1991, the organization supports immigrant families in reaching economic stability, including day laborers — often low-income immigrants from Mexico and Central America seeking short-term employment. As the daughter of Mexican immigrants, Cervantes was drawn to MI’s mission and started working at the organization as a volunteer. She is dedicated to increasing equity in the Latina/o/x immigrant community and advocates for participatory decision-making and the internal development of talent and leaders.

How It Started

Ever since I can remember — I can even date it back to kindergarten — I would always translate for my Spanish-speaking parents. Growing up, I was a translator, social worker, attorney, accountant — all of that! We did it for our parents because the language skills weren’t there. After all, the resource connections weren’t there.

My passion for my work dates back to those experiences. It’s also related to me being the oldest of four siblings. I was the first to attend college in my immediate and extended family. That was a pathway to open resources for my family because folks would come to me and ask how or where to apply. It’s how I was raised and who I was already becoming.

I moved to the Bay Area from Southern California, where I lived in the predominantly Black and Latina/o/x, very low-income city of San Bernardino. Unemployment, drugs, violence — all of that was prevalent in my life. I didn’t have an opportunity to visit the University of California, Berkeley before I decided to do my undergrad there. So, when I arrived, I was in complete culture shock. I hated Cal for the first six months as I struggled to connect because I didn’t see people like myself.

I came across the Multicultural Institute, which immediately opened my eyes to my community. I felt like it was my home away from home. MI was a place where I could finally feel like myself and not like an outsider. That drew me to volunteer for the mentoring after-school program at MI in 2010. And then, slowly, I became super invested. While volunteering at the Multicultural Institute, I talked to parents who spoke my language and reminded me of my parents, aunts and uncles. It allowed me to feel a sense of community far away from home.

Shortly after I began volunteering, I was asked to join part-time. Then, I started moving up through different positions. Once I graduated, MI offered for me to stay on board full-time as our first health and immigration program director. My main focus was providing health and immigration support and services to the day laborers in our low-income community. At that time, back in 2014, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was still new. So, I was helping folks sign up for health insurance or enroll undocumented folks who couldn’t apply for the ACA or Medi-Cal in HealthPAC — a low-cost health program for low-income Alameda County residents.

I continued to love the work. Eventually, I was offered the associate director position, primarily handling grant writing. I had no grant writing experience. At the time, I was not looking for a leadership opportunity. I went through a lot internally and didn’t think I could do it, but I took it on. The MI leadership believed in me. I did everything: development, grant writing, grant reporting, contracts, and money management.

After taking that role, I started supervising program staff and did most of our donor cultivation. I served in the position for nearly six and a half years. Then, I was part of MI’s leadership transition when MI’s former executive director and founder began planning for his retirement.

How It’s Going

I just celebrated my second year as executive director on July 1. It’s been a very wonderful experience. The first year was tough, but I’ve been able to do some amazing things while supporting our staff’s well-being and development. During my first year as executive director, we obtained full health benefits for everyone — vision, dental, chiropractic, acupuncture, and life insurance. We also have a 401K for the first time.

Our hybrid, flexible work environment is so important to us. I took on the role one year into the COVID-19 pandemic. So, I fully adopted work-from-home and flexible work schedules. That has made such a difference. I know it sounds so minimal, but for our team to feel like they can work from home has helped improve the organization’s culture, and people feel more supported.

We’ve also taken on a more community-centered approach. All of our work is conducted on street corners. Our staff goes out in the mornings to provide services to community members. When I came on board, I thought having a community center where folks could come inside was crucial. Although we’ve had courses and appointments onsite, we’ve never had a lobby space for people to gather. That’s one of the first things I did. We now provide complimentary coffee in the mornings at all of our locations. People can come in to charge their phones and use our restrooms. It’s something we’re so, so proud of. And finally, we continued to enhance our housing program and had our first open house a few months ago.

I’m proud of our dual focus: How do we serve the community more meaningfully and intentionally? And, how do we also take care of ourselves and the staff so they can feel good about themselves and their overall well-being and have more success at work?

Looking to the Future

We’ve seen a lot of community members take what they’re learning and put it to use. People have taken our GED courses and are now attending Mills College in Oakland or furthering their education in other ways. We have course participants who have businesses now. It makes me hopeful to see how our programs offer tangible next steps for their long-term future.

In the future, I would love to see more housing availability for us to increase our housing programming. And we want to continue providing more permanent jobs. We do a fantastic job offering short-term employment, but it would be great to give folks something permanent.

Speaking about the organization, I want to ensure we have a strong foundation. I’m very proud to say we have six months of operating reserves. But I want to ensure it’s two or three years of budget.

I would also love for MI to own a property in Richmond. We own our San Mateo and Berkeley offices but rent a space in Richmond. Although that’s great, it’s beautiful when you own a space and can do with it as you wish.

Michael Matsuda: Preparing Students for Prosperous Careers

Michael Matsuda is the superintendent of Anaheim Union High School District, a public school district serving several cities in Orange County, California. Matsuda worked for the district for 22 years before stepping into his current role in 2014. Since then, the district has adopted a new educational model incorporating career pathways in partnership with higher education and private and nonprofit sectors to boost student opportunities. In collaboration with CZI, Anaheim Union High School District is working with researchers at the University of California, Irvine, to study the impact of this career preparedness educational framework.

How It Started

I was named after the married white couple who financially and emotionally helped my parents, who were interned as Japanese Americans during WWII. This experience gave me a deep appreciation for the importance of community and compassion.

In fourth grade, my teacher, Mrs. Kranz, helped me recognize my strengths, assets and voice. She gave me the confidence to be creative and aspirational. These experiences inspired me to become an educator and to create a school where all students feel seen, valued and supported.

How It’s Going

I am most proud of making the 5Cs — critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, communication and compassion — an instructional priority. Compassion, especially healthy self-compassion, and self-love, is needed more than ever as young people navigate a world of uncertainty, volatility and fear.

We have also made great strides in closing the achievement gap. Students at our primary University of California (UC) feeder school, UC Irvine, have outperformed students from all other Anaheim districts (including districts with much higher socioeconomic populations) in cumulative GPA and persistence rates for three consecutive years.

Looking to The Future

Students are more resilient, compassionate and concerned about solving big issues than ever. I think Gen Z will significantly impact the world and teach the older generations a thing or two about being human.

LaKesha Roberts: Assisting Neighbors in Need With Compassion

LaKesha Roberts is the associate director of the Ecumenical Hunger Program (EHP). She began working at the organization as a volunteer and is passionate about serving her community and dedicated employees. For Roberts, working at EHP is more than a job. Its mission is to provide compassionate, dignified and practical assistance to families and individuals experiencing economic and personal hardship. The East Palo Alto, California, organization offers several programs, including emergency food assistance, resources for children, and advocacy. Ecumenical Hunger Program is one of CZI’s Community Fund partners.

How It Started

My interest in helping others started with my grandmother, Nevida Butler, former director of the Ecumenical Hunger Program and current outreach staff member. This was her life. Everything about her was EHP. Growing up, I was able to see the work she did and the impact it had. When I used to go to the grocery store with her, everybody wanted to stop and thank her for all that she’s done. It always warmed my heart. I could say it’s hereditary, as my mother and current EHP executive director, Lesia Preston, shared the same compassion and service for the community that was passed down to me.

I’ve volunteered in the program since my high school days at Eastside College Preparatory School in East Palo Alto, California. To be able to give my time and impact somebody’s life is something that has always moved me. Even in school, I was always willing to help or take time for others.

I remember being at EHP during the holidays one year, and news reporters were interviewing a family about our Christmas program and its impact. A dad and his son were answering questions, and the little boy said he only wanted an iPod for Christmas. I overheard the interview while listening to an iPod and packing gifts and felt terrible. Here’s a kid who really wanted one, and because of the family’s situation, he would never be able to afford it. So I thought, “Can I give him mine?” We ended up having iPods as Christmas gifts, so we gave him one.

I wasn’t planning on coming back to EHP to work. When I went to school, I studied math and education and was set on being a teacher. But after four years of my education minor and going out to schools, I realized I didn’t want to be a teacher anymore. It wasn’t because it wasn’t great; I simply didn’t see myself in a classroom. If you’ve ever been fortunate enough to experience the culture of EHP, you would understand that it’s a feeling like no other.

When I finished at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, I moved to Texas to live with my grandmother after she retired. I worked in an emergency shelter. She became sick and returned to California, so I followed. That same weekend I returned to California, it was EHP’s community block party event. The receptionist had found a new job, and I offered to fill in since I was between jobs. From there, I ended up staying. I worked in several positions — part-time in the food closet, donation pickups, full-time program manager, etc. — before I arrived in my current position as associate director, which the EHP board created for me.

How It’s Going

I’ve been fortunate to be able to work with the Ecumenical Hunger Program for over a decade and counting.

I don’t know when we can say we’re out of the pandemic, but surviving that is probably my most significant accomplishment at EHP. Before COVID-19, we were serving 100-120 families a day. When COVID hit, we were serving 300 families. And on our highest day, we served more than 400. It got really busy here. We shut down all of our services in the warehouse and only focused on food because that’s what our families needed at the time. We had lines wrapped around the block day in and day out — in the heat. We moved everything outside to serve community members safely in the parking lot, which is how we created the drive-thru service.

We also changed our scheduling from a five-day operation to three days a week so we could go strong and then give the staff a break. EHP still paid for the full five days because we value their work and dedication. The team here worked incredibly hard. Getting through COVID and having the staff still be here, in addition to keeping up with and managing to serve all the families that we did, is a huge accomplishment. I’m very proud of that.

Our organization works hard to be open and serve everyone. We don’t turn away anyone — and we never want to. We want everyone to feel comfortable to receive services here. Even if from out of our area, we serve anyone who comes and help them connect to other resources that will be more beneficial to them. We work closely with our families and try to engage with them as much as possible to determine their needs and ensure we meet them. EHP also partners with other agencies in our community to ensure that we are not duplicating their efforts, but to find out how we can all be a part of the solution for the families we’re serving.

Looking to the Future

The pandemic showed us that no matter what is thrown at us or the obstacles we face, we will figure out a way to keep pushing forward.

Right now, we’re going through some serious changes, and EHP is working on providing solutions to supply our clients with the food servings and provisions they need.

Since the pandemic, we have been surviving off the partnerships of the food bank and other neighboring partners for our food supply. However, due to the toll of the pandemic’s aftermath, we’ve not been able to provide our family with the necessities they’re now accustomed to. We’ve been purchasing food every month — thousands and thousands of dollars of food that we never had to buy before. So, that makes it all scary. Still, I have hope. We genuinely value our donors who have come to the forefront and did everything they could to ensure we were supported during that time.

In the future, we want to create a client-choice shopping experience where our families can essentially shop in a free grocery store. That goal was put on hold when the pandemic happened. While many have expressed that our drive-thru is quick and convenient, we want to give them the option to shop if interested.

Eddie Lincoln: Increasing Equitable Enrollment in Rigorous Courses

Eddie Lincoln is the chief executive officer of Equal Opportunity Schools (EOS). He is passionate about issues of social justice and educational equity and closing the opportunity gap for youth who are historically overlooked. Before his current role, Lincoln was the assistant director for K-12 partnerships at the Seattle University Youth Initiative. Equal Opportunity Schools is a Seattle-based nonprofit that collaborates with schools to increase equitable access to college- and career-prep secondary school courses for underserved and underrepresented students. Last year, CZI partnered with EOS to scale its approach.

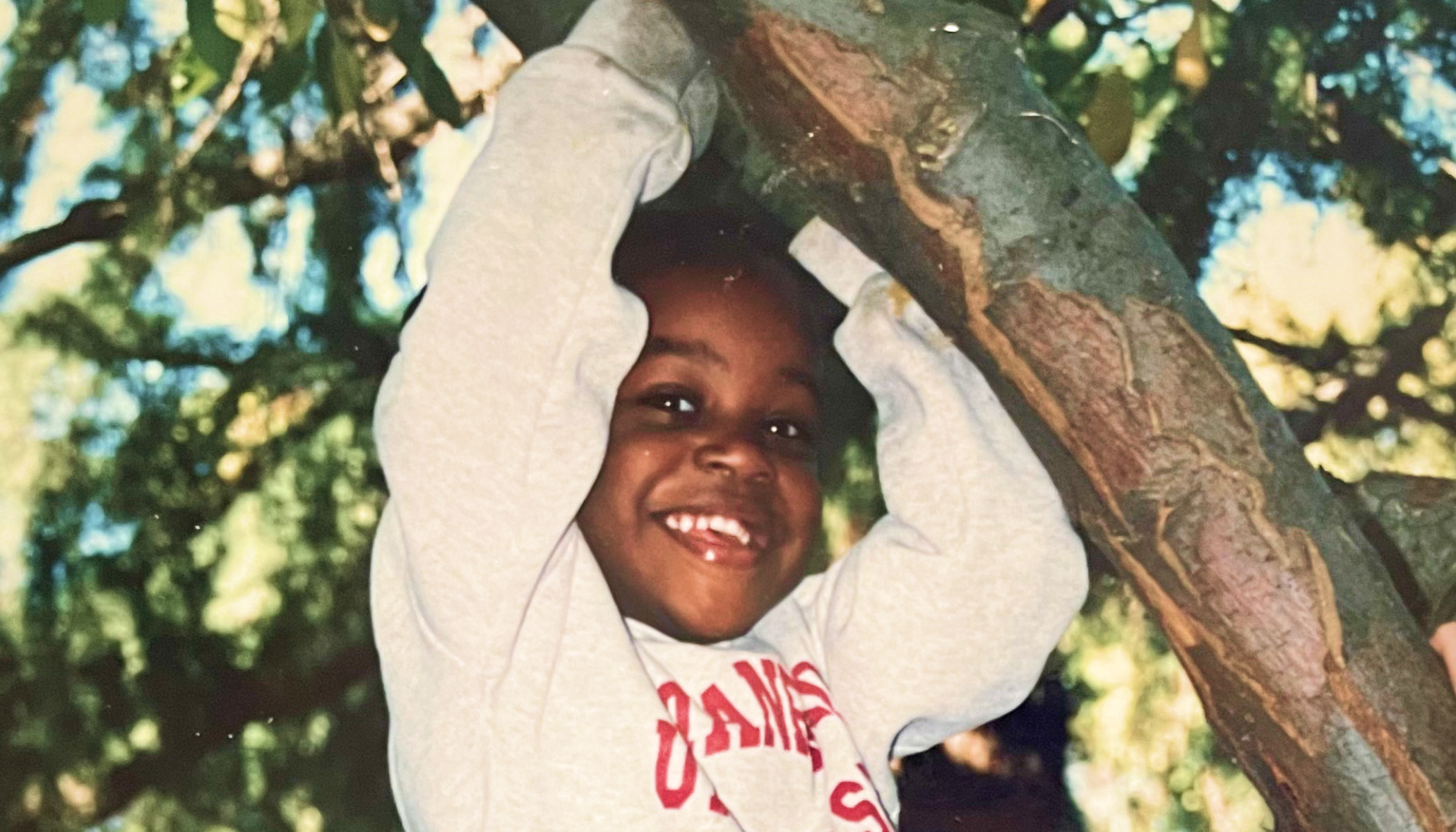

During my childhood, I was an athlete who traveled weekly to play basketball throughout the country from April to September. For most of my adolescence, I considered academics secondary. I attended college, but my primary focus centered around playing D1 basketball.

When I reached my senior year of college, my body began to feel the strain of being an athlete. I had to think about my future beyond basketball. The truth is I felt confused and unsure of what direction to take.

Two African American law professors at my university encouraged me to attend law school. Following my conversation with them, I contacted my childhood basketball coach, Kevin Davis, who I remembered had a law degree. He also explained how a degree of this type would benefit me long-term.

I went on to earn a Juris Doctor from Texas Southern University.

As a law student, I realized I had the potential to be a leader. I also learned that I had the power to make a difference in the world. After graduating, I got a job in the nonprofit education sector. I fell in love with my work and devoted my career to education equity.

When I joined EOS nine years ago, I never imagined I would become the CEO. I also did not expect the organization to grow from 14 to 90 employees and 39 to 900 school partners during that time. In the past 11 years, EOS has provided access to AP, IB, and dual enrollment courses to more than 70,000 students across 35 states.

One of the reasons for my success as CEO is my commitment to continuous learning. I have found mentors who support me in the areas where I need to grow. Additionally, I have developed a network of CEOs with whom I keep regular contact.

I am not the same person I was as a young athlete. I’m more confident, more resilient, and more passionate about making a difference. I’m grateful for the journey that has brought me here, and I’m excited to see what the future holds.

If I could go back in time and give my younger self some advice, I would say:

- Do not let your upbringing and environment determine who you become. There is no doubt that you are an exceptional athlete, but you are more than just that. The talent and brilliance you have are truly remarkable.

- Be bold and break against the norm. Your interest in murder mysteries, civic engagement and politics may appear uncool. However, you will lead an organization that inspires thousands of young people to embrace their authentic selves and pursue their passions.

- Your example will inspire students to believe they can accomplish anything they want. Stay strong in all that you are, and know that you have such a beautiful life in front of you. I am so proud of you.

Dr. Christina Cipriano: Helping Educators Support Student Well-Being

Dr. Christina Cipriano is an assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine’s Child Study Center and the director of the Education Collaboratory. She is a developmental and educational psychologist who leads Project Flourish — a CZI-supported effort to develop measurement tools that K-12 schools and families can use to help young people develop their individuality, learn problem-solving, and form healthy relationships with their family members, peers and teachers. Cipriano is a national social and emotional learning expert, having worked in classrooms with diverse populations, providing training to educators and support staff and direct instruction to students.

My advice to my younger self: Don’t hold back. The unique vantage point you bring to the spaces you occupy is valuable.

Get comfortable in the discomfort. Doing work that departs from the status quo requires risk-taking and learning to grow in new territory. Concurrently, seek to see opportunities in discomfort and risks.

Ask yourself:

- How can I learn from this challenge before me?

- What can I offer to support continual change?

- Who are my sponsors, allies and critics in this work, and how can I learn from each of them?

Stay motivated. I have the honor of being the mother of four beautiful, curious, energetic and compassionate children (currently ages 11, 9, 8, and 4) who deserve to grow up safe to learn and thrive. No matter what challenges are to come, I am confident that together, we can indeed build the world we want all our children to thrive in.

All of this has set me up for where I am today. I recently completed an update and evolution of the social and emotional learning (SEL) field’s seminal paper titled “The State of the Evidence for Social and Emotional Learning: A Contemporary Meta-Analysis of Universal School-Based SEL Interventions.”

The impact of this body of work is multidimensional.

First, there is what we did — amass the largest and most comprehensive body of evidence to date for understanding the skills and mindsets involved in the social process of learning and development.

Then there is what we found: If you look at all the evidence for grounding education in human development — mental health, physical health, emotional well-being — you see an overall effect on positive outcomes that matter for kids worldwide. That is huge and unexpected, given the variability in the field and the quality of programs and studies.

Then, there is how we did it: This is the first registered report of evidence synthesis to be published in the field’s top journal — and now serves as methodological precedence and the foundation from which to build what we know works for whom under what conditions.

Reflecting full circle on my career so far, I didn’t set out to be a meta-analyst. I’m invested in supporting the flowers rather than the forest. But it needed to be done, and it needed to be done with equity and inclusion at the center. For that reason, we went forth and built a new pathway of evidence generation.

Not only would my younger self be surprised at my chosen career, but also be proud that I’m a runner. In high school, I leveraged every possible enrichment and social opportunity to get out of participating in gym class. Now, I can say at 39 years old, I ran my first marathon: the Boston Marathon. I ran it in honor of my 11-year-old son, Miles, to raise awareness about his horribly regressive rare disease, Phelan McDermid Syndrome, and to fundraise for his incredible school, the Campus School at Boston College.

Meet More Voices of Change

CZI partners with people and organizations working to build a better future for everyone through science, education, and supporting our local communities. We collaborate on bold ideas that have the potential to accelerate social change.

Read more stories featuring incredible change-makers and ground-breaking research.