May 7, 2020 · 14 min read

They’re the Face of COVID-19 Response. They Also Have DACA Status.

Right now, nearly 700,000 immigrants with DACA status are waiting for the Supreme Court to render a decision on Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California. The case will decide whether these young people are allowed to renew their status and continue working, or whether they face risk of deportation.

The case will also have profound implications for America’s response to COVID-19—because 29,000 DACA recipients work in health care fields. We spoke with four of them about their work during the pandemic, their perspective on the Supreme Court case, and their hopes for the future.

Jesus Contreras

Jesus Contreras is a paramedic based in Houston, Texas.

What drew you into this work?

I grew up undocumented in Houston. During my senior year of high school, I chose to take an elective EMT basic program class that was offered through a local community college, just to see what it was about and what I could do with it.

I ended up falling in love. And so I studied hard, did well in the class, and was one of a few people that was eligible to take the national registry exam for EMT basics. However, to take that exam, you have to have a driver’s license or other government identification. Of course, I was undocumented so I didn’t have any of that. And despite how well I’d performed in the class, I couldn’t do it.

This moment stuck with me. Something I wanted to do, I couldn’t do because of my legal status. But I moved forward. I went to college. Eventually, the Obama administration created DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which helped a lot of us pursue the things that we wanted to pursue. For me, that was my career in EMS. When [DACA] happened, I decided I wanted to come back to Houston to finish the EMT basic exam and then move forward with the paramedic program.

The rest is history. I became a paramedic. And since then, I’ve been able to help people in need. It’s a tough job. But it’s rewarding, especially if you’re a people person like I am. Being able to talk and connect with people of all sorts of different races, religions and political backgrounds, to me, is special.

What does a day of work look like right now?

Every day is different. But we know one thing: going into work we’re going to be dealing with sick people. We’re going to be dealing with dying people. We’re going to be dealing with people that are having the worst day of their lives. We absolutely know we’re dealing with that.

I work 24-hour shifts on Wednesdays, and then I work a 32-hour shift on Saturday through Sunday. At the moment, the thing that has changed is that we are taking a lot more precaution with patient contact, and we’re trying to minimize the amount of contact and spread of COVID or any COVID-like patients. Everything takes a little bit longer, and you’re a lot more aware of what you’re touching, what you’re seeing, what you’re smelling. It’s an adjustment for a lot of us, especially with our treatment plans. We’ve never dealt with anything like this before.

But we’re professionals, health care professionals, for a reason. We understand that we can tackle this if we prepare correctly and have the right equipment. It’s very intense, but I’m faithful. I love what I do. So I do my part to help where I can. And I know there’s a lot I can do to comfort and give those patients with COVID-19 some peace of mind and some assurance that things can get better.

What do you hope the public understands about DACA recipients, and the case the Supreme Court is about to rule on?

I hope people understand that DACA recipients are essential workers, in health care and in other important roles in the country. That we bring so much revenue and boost the economy and have so many positive effects in the country, and a lot of the negative things that are said about us aren’t really true.

Hopefully, people see that those health care workers and essential workers you’re hearing so much about on the news, a large number of those workers are DACA recipients, and are immigrants.

[I hope they understand] that ethically and morally, [protecting DACA is] the right thing to do—to welcome those that want to be productive and want to be a part of the community. And hopefully, people see the work that we’re doing. Hopefully, people see that those health care workers and essential workers you’re hearing so much about on the news, a large number of those workers are DACA recipients, and are immigrants. And hopefully, people can understand and relate to us as people that matter, not just as numbers or statistics.

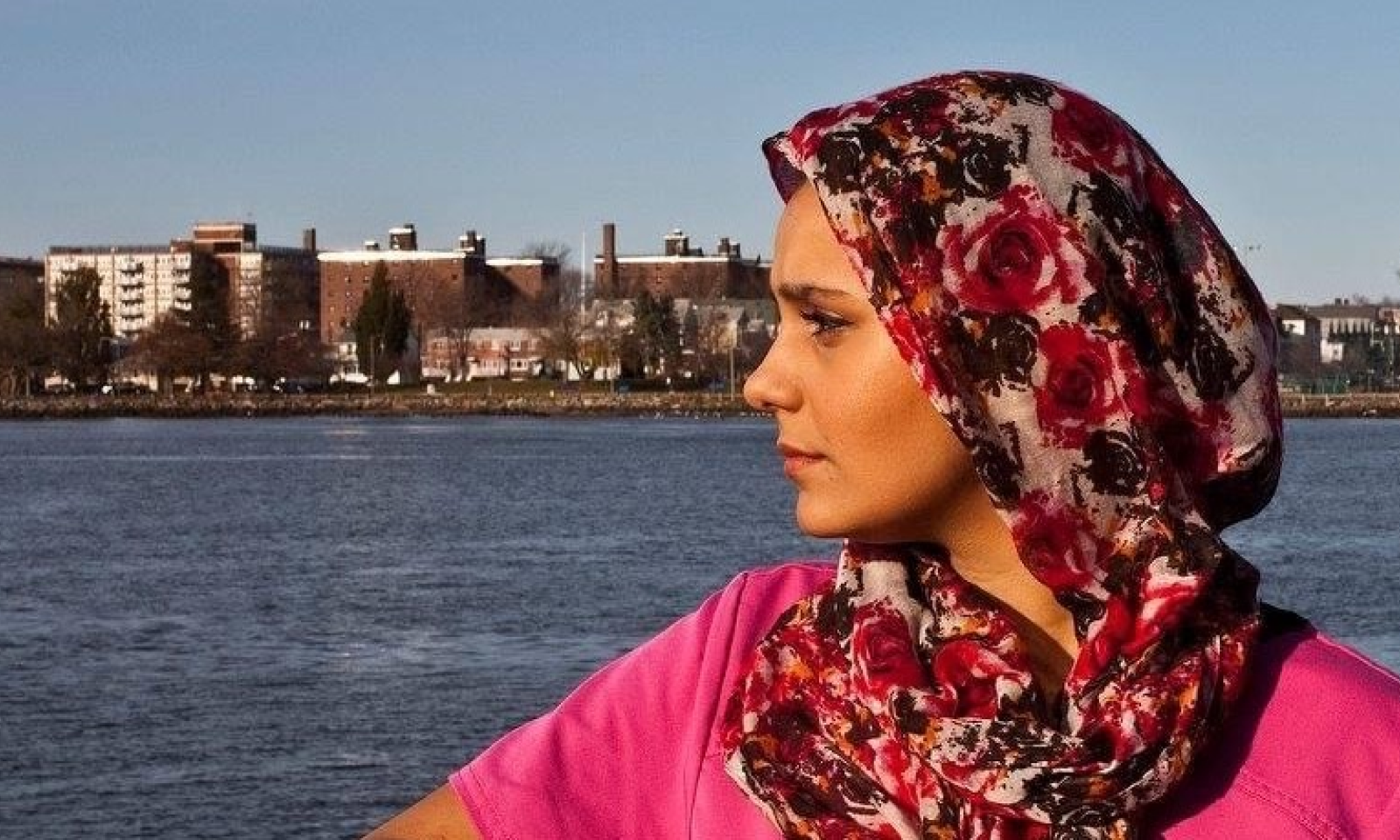

Hina Naveed

Hina Naveed is a registered nurse who works with children in foster care, and a volunteer with the Medical Reserve Corps. She is also the co-director of the Dream Action Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for fair immigration policies, and a part-time student at the CUNY School of Law.

How did you decide that you wanted to pursue a career in health services?

I first came to this country from Pakistan when I was ten years old, [so my family could seek treatment for my older sister’s life-threatening brain condition]. At the time, I was too young to really understand what we were going through. But I do remember a time when we rushed to the ER because my sister was having multiple strokes.

I remember sitting in the hospital room, feeling so stressed and confused about what was happening while my parents spoke with the doctor. And then a nurse came over and spoke to us. She was so compassionate and so kind; she calmed me down and made me feel safe.

That’s when I knew no matter what I did or where I ended up, I wanted to do that for someone else. I wanted to give that sense of relief, that compassionate care in the midst of crisis.

What does a typical week look like for you during the COVID-19 crisis?

I’m a registered nurse who works with foster children. So Monday through Friday, I’m supporting families and coordinating care. At the foster care agency, we’re addressing the emotional toll that this is taking on children and their families and providing medical support during a time when there’s so much uncertainty.

On weekends, I volunteer as a nurse with the Medical Reserve Corps, and they place me in different organizations. Right now, I spend one day at a hospital and one day in a residential center.

In a hospital setting, there are a lot of acute patients, so you’re constantly hearing “Code Blue” over the speakers and calls for support. Each time I’ve volunteered, I’ve been with COVID patients. And with all the PPE—the N95 masks, the surgical masks, the face shields, the two sets of gowns, the two sets of gloves – going into a patient’s room to provide support and medication is an undertaking. It makes me feel for those nurses in the Medical Corps who are doing this three, four, five days a week.

The residential facility looks a bit different. The residents live there—it’s their home. So I see a lot of grief with residents who have lost a neighbor down the hall, staff members who have lost residents whom they’d known for a while. The media has paid a lot of attention to frontline workers in hospitals, but residential care facilities have also been hit hard. They’re understaffed and often not getting the recognition they deserve.

If there is one message that you want to put out there for the Supreme Court to consider as they weigh this decision, what do you hope that they know?

I want the Supreme Court to think about [what it would mean if] each DACA recipient [were] deported, and what a hole that would leave in each person’s universe, in each person’s community. Not just DACA recipients who are nurses like myself or EMTs like Jesus, but [other] essential workers—the farmers, the sanitation workers, the grocery workers, all of us who put ourselves on the line every single day to contribute to our communities and our country. And I want them to think about how much worse that impact [would] be due to the fact that we’re in the middle of a pandemic, when [health workers] are actively saving lives.

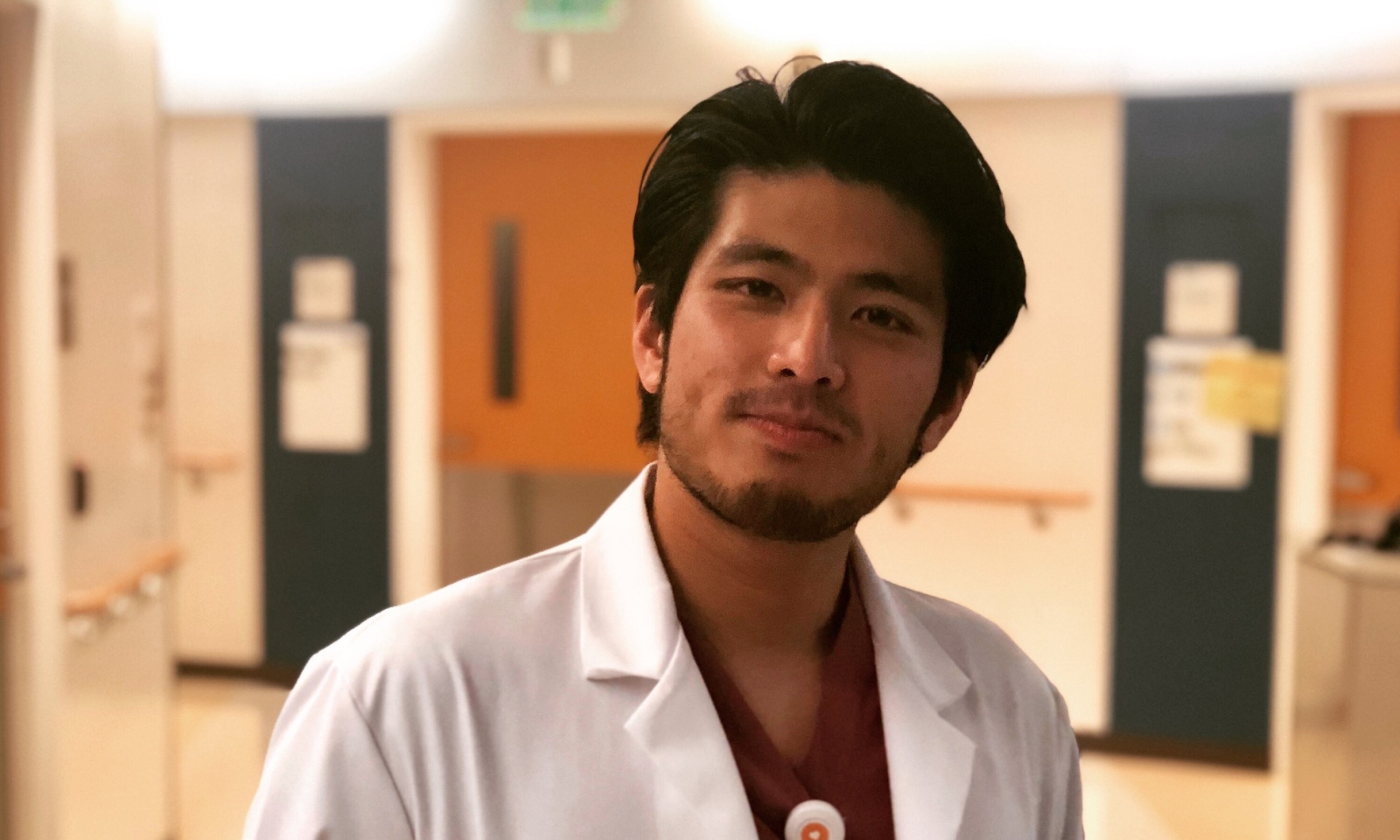

Dr. Jirayut “New” Latthivongskorn

Dr. Jirayut “New” Latthivongskorn is a resident physician in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at San Francisco General Hospital. He is also the cofounder of Pre-Health Dreamers, a nonprofit organization that supports undocumented youth who are interested in medical professions.

When there isn’t a pandemic going on, what’s your job like day-to-day?

I have the privilege of taking care of patients who are the most marginalized and underserved in the [San Francisco] Bay Area. And as a resident in family medicine, I’m learning and growing to become the clinician that I have always wanted to be.

What that means day-to-day is I show up to work about 80 to 100 hours a week. [Family practice residents] rotate through different departments—learning pediatrics, taking care of kids, working in women’s health. Currently, I get to deliver babies and share that joy with their parents. I take care of other patients, too, including my own private care set of patients.

Do you remember how you felt when you first started hearing about COVID-19?

At the beginning, it really felt overwhelming. We had this ominous sense of what was coming. Our hospital and clinic tried to reorganize our systems as much as possible. We started cancelling outpatient visits that weren’t urgent, and shifting to telephone and virtual visits. And on the inpatient side, we created new teams to get ready for COVID-19 patients. So it certainly felt like we were working against time to beat the surge [that might be coming].

In San Francisco and the Bay Area, we’ve seen a steady climb in numbers of cases—but not yet [the kind of] surge we’ve seen in many other places. So we’re in this limbo spot. It’s somewhat manageable, [but we’re] still worrying about when it’s going to get worse.

How are you dealing with the uncertainty around the Supreme Court case? Do you try not to think about it, or is that impossible?

I oscillate [back and forth]. And I think that is, in large part, because there has been uncertainty around [DACA] for quite a while. It’s a coping mechanism to forget about it. I’m fortunate that I’m able to focus on the work that I get to do, which is to be a doctor and work with people.

Then there are moments where I come to, and there’s a resurgence of the reality that DACA is hanging by a thread, and any day now there’s a decision that could be made that could really jeopardize my own future and the well-being of millions of people.

Then there are moments where I come to, and there’s a resurgence of the reality that DACA is hanging by a thread, and any day now there’s a decision that could be made that could really jeopardize my own future and the well-being of millions of people.

So, certainly, that’s very overwhelming. The way I deal with it is to build community with friends and family to really support one another, and through my work as well—to make the changes around me that I can. Whatever happens, we will have to move forward.

If you had one thing that you wanted people to hear—to know what this moment is like for you and other people who are recipients of DACA—what would it be?

I want to share how most DACA recipients who are able to continue working—the almost 30,000 of us who are in health care, but also many more who are essential workers—we’re continuing to show up. This pandemic is just another example of DACA recipients doing what we’ve always done. We show up and show that we are a part of the fabric of America.

We can only hope that that is recognized by the current administration and the Supreme Court Justices. That’s all that I hope for in this uncertain time.

Denisse Rojas-Marquez

Denisse Rojas-Marquez is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She is also the cofounder of Pre-Health Dreamers, a nonprofit organization that supports undocumented youth who are interested in medical professions.

How did you decide that you wanted to pursue a career in health care?

There are two experiences that really stand out for me. One, I was a teenager and a family member had gotten ill. She was eventually diagnosed with gastric cancer and, unfortunately, passed away subsequently three months later. I remember asking my family: why did this happen all of a sudden? And it turned out that she had been having symptoms for some time but because of the fear of medical bills and going to the doctor, she never mentioned anything. I think that was the first time I realized just how costly the medical system was and what it could lead to.

The other moment that stands out was when my mother had gotten sick and was denied care. Because of her preexisting condition, she was ineligible for the insurance that we had found, and she was also not eligible for Medi-Cal because of our immigration status. When I realized that she could not obtain health care in the United States, I was shocked. There were hospitals right down the street from us that could’ve performed the surgery she needed. That was so hard, to see her go through that and be denied health insurance.

And today, you’re a medical student. What has your experience been like lately, particularly with respect to COVID-19 and the Supreme Court case?

When we started to understand the scale of [COVID-19], I knew that I could put my skills [as a medical student] to use. There have been a lot of volunteer opportunities with the medical school, and I’ve signed up for a lot.

One thing I’m doing is communicating with vendors who reach out to the hospital for PPE supplies—respirators, N95 masks, ventilators, goggles, and other supplies that medical professionals need. I don’t have any decision-making power, but at least I help get the information organized for people in the hospital. And I feel like I’m making a difference. As a team of volunteers, we’ve helped the hospital get more ventilators and masks to health care providers.

It’s scary. I feel nervous about my own safety in the United States, [and the threat of deportation]. But I also feel blessed that I can use my knowledge and skills in this time to help others.

If there is one message that you want to put out there for the Supreme Court to consider as they weigh this decision, what do you hope that they know?

My hope is that the Court understands the role that we’re playing now in this crisis. There are 29,000 DACA recipients in the healthcare profession, and over 200,000 who are currently filling essential roles in the COVID crisis.

I talk to people every day—people who are working as physical therapists, nurses, food suppliers—who are helping during this crisis because we care and because we consider the United States our home. This has been our home for so many years. I’ve been here for 30 years now, and I can’t imagine living anywhere else. I hope the Court understands the people behind the numbers and knows that we truly care about the country and hope to stay.